A Brief History of Brooklyn Cocktails

Including the Luckless History of The Brooklyn Cocktail; and a Possible Chicago-Brooklyn Hotel Cocktail Connection.

Nobody talks about the Brooklyn cocktail scene.

I don’t mean the current scene; that gets plenty of press, and has since the late aughts when the first craft cocktail bars opened in the Borough of Kings.

I mean everything that came before that. Reams have been written about the many saloons, boîtes, clubs and hotel bars that have dotted the Manhattan landscape since the early 19th century. But little has been put on paper about the elevated drinking options of the city’s most populous borough.

Recently, I was asked by the Montauk Club to deliver a talk about cocktails. The Montauk Club was founded in 1889 and is housed in a remarkable Venetian Gothic building just off Grand Army Plaza. Since it is a Brooklyn-based organization, it only made sense to make Brooklyn cocktails the subject of my lecture. This gave me the opportunity to dig into what exactly constituted the Brooklyn cocktail world before the modern likes of Clover Club, Maison Premiere, Dram and Fort Defiance opened up for business.

Any talk about Brooklyn cocktails must first address The Brooklyn Cocktail—that is, the cocktail that most commonly goes by that name. But doing so immediately brings up the central paradox of Brooklyn cocktail history: that much of it has one foot in Manhattan.

The first widely known drink to go by the name Brooklyn appeared in 1908 in Jack’s Manuel, a book by Jacob A. Grohusko, a Manhattan-based bartender who lived in Hoboken, NJ. Grohusko was born to Russian-Jewish parents in England and lived until 1943. (He is buried in Beth David Cemetery in Elmont, Long Island.) He was an ambitious sort; he updated his book three more times during his career.

His Brooklyn Cocktail is made of rye, sweet vermouth and touches of maraschino liqueur and Amer Picon. As such, it is not much different from the Manhattan, which had been going strong for more than two decades by the time Grohusko’s book came along. It could accurately be called an Improved Manhattan Cocktail.

The history of Grohusko’s Brooklyn Cocktail is largely one of Failure to Launch. It never really caught on, though Chicago hotel man Jacques Straub put it in his 1914 book Drinks—albeit with dry vermouth, not sweet, a translation error which, as we will see, caused problems later on.

The drink was poorly enough known in 1937 that The Brooklyn Eagle, the borough’s primary news order, declared that the Brooklyn Cocktail concocted by Brady Dewey at the long-standing downtown restaurant Gage & Tollner was the true Brooklyn Cocktail. That drink was completely different from Grohusko’s, being made of Jamaican rum, lime juice and grenadine.

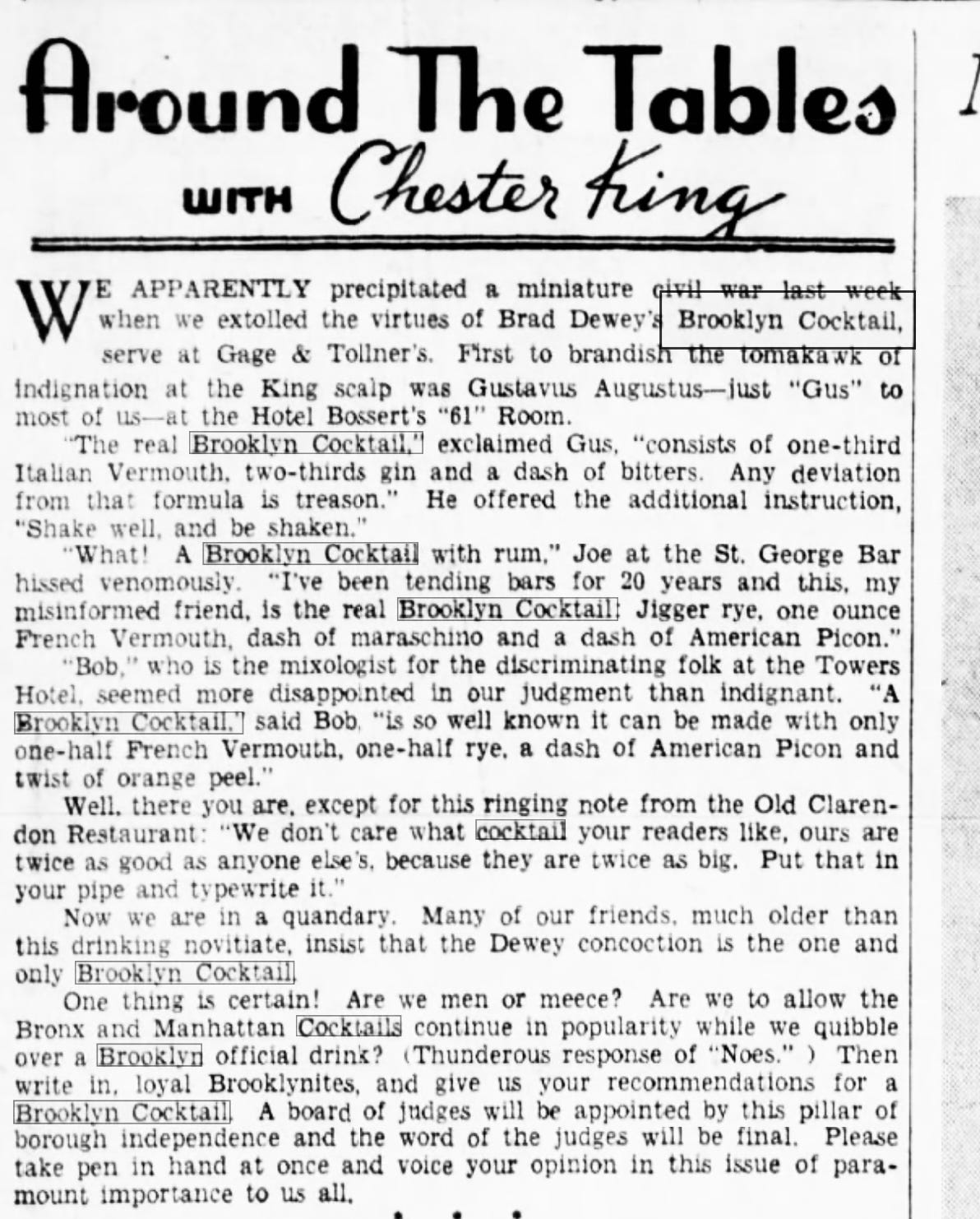

It was Eagle columnist Chester King who reported this news. The negative reaction from the Brooklyn bartending community was such that King was compelled to run a follow-up column, in which he gave space to the various bartenders’ objections.

Gus at the “61” Club in the Bossert Hotel declared a real Brooklyn Cocktail to contain gin, sweet vermouth and a dash of bitters. Joe at the bar at the St. George Hotel said the drink called for rye, French vermouth, maraschino and Amer Picon—a drink very like the Straub version of Grohusko’s Brooklyn. (Hold that thought. We’re going to come back to it later.) And Bob of the Towers Hotel bar said the Brooklyn was made by combining rye, French vermouth, Amer Picon and a twist of orange peel.

The takeaway from all this: there was no agreement in Brooklyn bartending circles as to what a Brooklyn cocktail was.

King’s column ended with this call to arms: “Are we men or meece? Are we to allow the Bronx and Manhattan cocktails continue in popularity while we quibble over a Brooklyn official drink?”

Fortunes didn’t improve much for the Brooklyn Cocktail in the decades to come. Indeed, the situation is just as bad today. The main problem is that Grohusko unknowingly doomed his drink to obscurity by including Amer Picon. The French aperitif stopped being available in the United States decades ago; moveover, the formula was changed in the 1970s.

A wholly different Amer Picon than the one used in Grohusko’s day basically meant Game Over for his Brooklyn Cocktail. That didn’t stop American mixologists during the aughts from trying to approximate the liqueur with other ingredients. But most of those experiments to recreate Amer Picon—and the subsequent reworkings of the Brooklyn Cocktail—failed to impress the public.

In 2012, I attended a seminar at the short lived convention, Manhattan Cocktail Classic. It was titled “Do Not Resuscitate” and the subject was old cocktails that bartenders thought did not deserve a revival. Here’s what I wrote at the time in The New York Times:

A few of the darlings of the cocktail renaissance took a heavy drubbing from the panel. Among them was the Brooklyn cocktail. Entirely obscure a decade ago, this mix of rye, dry vermouth, maraschino liqueur and Amer Picon (a French amaro), can now be found on bar menus across the United States. “This is not a good drink,” St. John Frizell said with unhesitating definitiveness. As the owner of a Brooklyn bar, Mr. Frizell has seen his share of Brooklyn cocktails. Most of said concoctions bend over backwards to make up for the fact that you can no longer buy one of the drink’s key ingredients, Amer Picon, in America. “Drinking a Brooklyn makes you think, ‘Why am I not drinking a Manhattan?’ — a drink for which the ingredients are readily available,” he said.

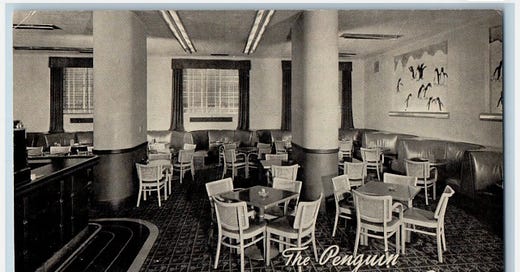

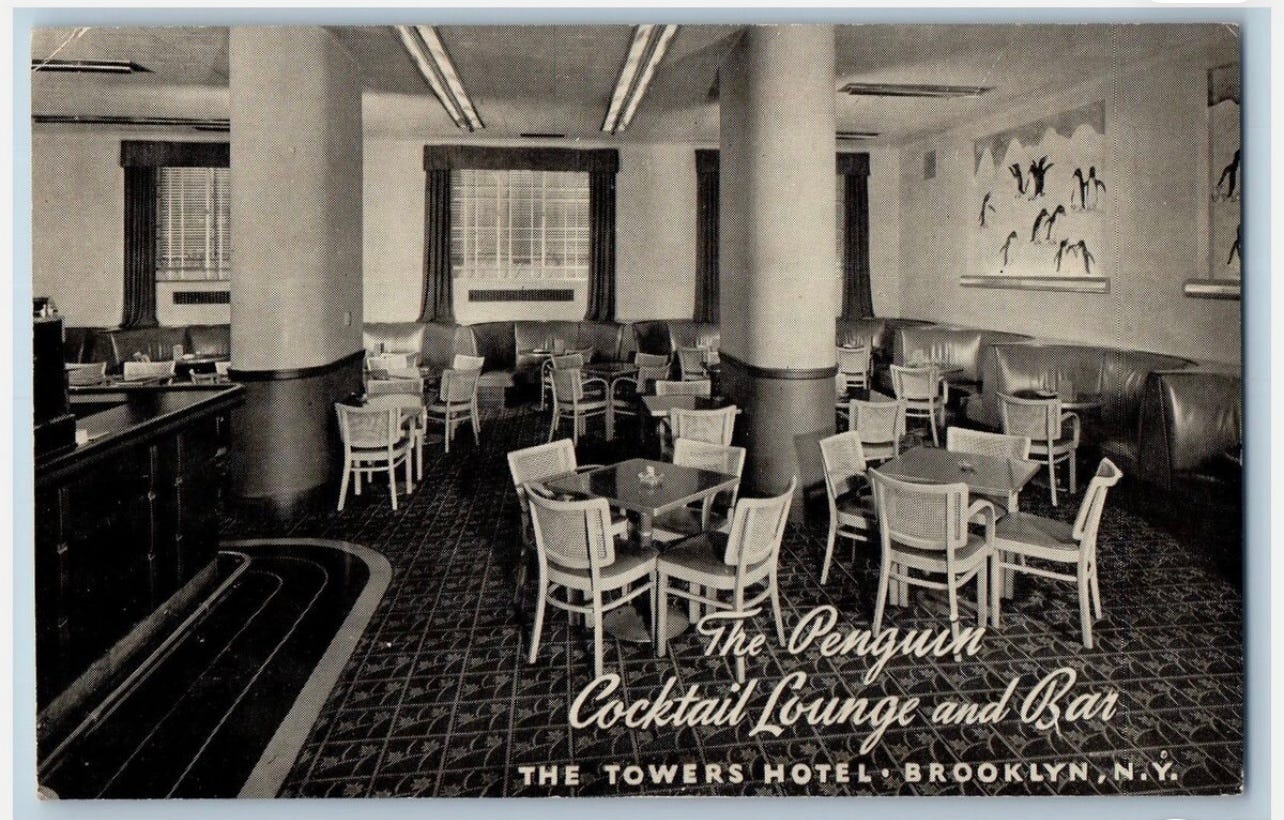

But let’s return to the Chester King column from 1937, for it is an indication where a Brooklyn reporter might turn for answers to cocktail questions. Three hotels are mentioned: the Bossert, the Towers and the St. George. All three stood mere blocks from one another in Brooklyn Heights, the borough’s first and fanciest neighborhood. Each hotel had a bar well known to the public. The Bossert has the “61” Room. The Towers had the Penguin Cocktail Lounge and Bar. And the St. George—the biggest and most famous of the all—had the St. George Cafe and Bar.

I tried to locate menus for these bars, to better learn what sort of drinks they served, but could find nothing, aside from the fact that you could get Martinis, Manhattans, Daiquiris, Old-Fashioneds and high balls at the St. George. (No mention of a Brooklyn Cocktail.) In fact, the only mention I could dig up of a cocktail unique to the St. George came from an unlikely place.

A couple years ago, I was given by antiquarian bookseller Lizzy Young a 1934 promotional booklet put out by Seagram’s. It was titled “Fun at Cocktail Time” and including dozens of drink recipes supposedly served at various famous bars, restaurants and hotels across the United States.

I regarded the volume with suspicion because every drink in the book miraculously contained a product made by Seagram’s. More likely than not, Seagrams’ PR department dreamed up the special house drinks for these establishments.

Still, it is the only piece of cocktail literature I own that mentions the Hotel St. George. And, according to Seagrams, one of the signature drinks at that hotel was the Millionaire Cocktail, a little item made of rye, curaçao, orange bitters, grenadine and egg white. The drink is credited to “Rudolph Letsch, Catering Manager.”

It didn’t take long to establish that Rudolph Letsch was a real person. He was written up often in the New York press. And he wasn’t the only Letsch in the hotel business. There were four Letsch brothers: Carl, Rudolph, Paul and Hans. And their career paths were akin to a mother duck and her ducklings.

The Letsch brothers were from Germany, where their father owned a large hotel. The sons were all brought up in the hotel business from a tender age. All four sons moved to Chicago in the early 1900s and all four worked, at one point or another, at the Blackstone Hotel.

Cocktail history buffs will recognize the Blackstone as the place where Jacques Straub was employed when he published Drinks. That means, at the very least, that Carl—who was the oldest Letsch brother, born in 1891, and worked at the Blackstone in the 1910s—would have known of Straub and likely worked with or under him.

All of the Letsch brother eventually moved to New York and three of them—Carl, Rudolph and Hans—got jobs at the St. George. Carl was general manager, Rudolph catering manager and Hans chef.

All of this history lends the inclusion of the Millionaire Cocktail in the Seagrams pamphlet more credence. That’s because the recipe in the booklet is none other than the one found in Drinks by Jacques Straub. There were many cocktails that sailed under the name Millionaire in the early 20th century, but the Letsches of St. George chose to serve the one authored by Straub.

(I tried this Millionaire Cocktail and unfortunately it does not work. The egg white makes no sense in a cocktail since there is no citrus component, and there is not enough of a sweet component.)

A Blackstone-St. George connection would also explain why the St. George served the version of the Brooklyn Cocktail recipe offered in Straub’s book, and not the original created by Grohusko, as was made clear in the 1937 Brooklyn Eagle article.

There is only one other Brooklyn establishment listed in the Seagram’s booklet. That is the curiously named Villepigues in Sheepshead Bay. Their house cocktail was the Sheepshead Bay Cocktail, a name that seems a little to on-the-nose to be real. But the ultimate legitimacy of the Millionaire Cocktail at the St. George had panned out. So I surmised that a little digging into Villepigue was in order.

The restaurant was named after a South Carolinian of French descent name “Big Jim” Villepigue. (The pronunciations of this surname are myriad, so your guess is as good as mine). When Jim was 30, he married Sarah, then only 15. Sarah was shrewd, however, and urged her husband to open an eating establishment in Sheephead Bay, which was in the late 19th century home to a racetrack and a playland for the rich.

With the help of a loan from “Diamond” Jim Brady, he opened Tappin’s Hotel in 1896 and did exceedingly well. Soon, Villepigue’s restaurant was a favorite of the Whitneys and Vanderbilts, as well as celebrities like boxer Jim Corbett and stage actresses Marie Dressler and Nora Bayes.

Brady supposedly cemented Villepigue’s reputation for what they called “Shore Dinners.” Brady showed up one day to check in on his investment and asked for dinner. Not knowing what to serve the famously inexhaustible eater, the kitchen sent out everything and anything.

From there on in, Villepigue’s served a single meal and it was one of abundance. It began with lumps of crabmeat on bed of lettuce; then came clam chowder; soft shell clams with “Babcock sauce”; lobster or chicken served with vegetables and corn on cob, when it was in season; a side of Virginia ham; dessert; cheese; and coffee. Ah, the Gilded Age.

According to a 1934 restaurant guide called Tips on Tables, a meal at Villepigue’s lasted two hours and cost only $2.00. (Thanks to food writer William Grimes for this info!)

In 1914, Jim and Sarah closed up shop. But Jim grew bored and, in 1919, he reopened as Villepigue’s Inn at the corner of Voorhees and Ocean Avenues. He was just in time to host Tammany Hall-backed Mayor John Hylan and his cronies for a liquid bash on the eve of Prohibition. That scandalous dinner made headlines for days to come.

Jim enjoyed the good life as much as his patrons. He reportedly weighed in at 400 pounds. (Ironically, Big Jim’s great-grandson, also named Jim Villepigue, has made a name for himself as a fitness guru.) Still, he managed to live to the ripe old age of 76, when in 1926 he keeled over in the Hotel Pennsylvania. He’s buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. Sarah ran the restaurant until she died in 1934 and their don Adolph carried on until 1941, when Villepigue’s finally gave up its position as a Brooklyn institution.

So, about that Sheepshead Bay Cocktail, which made it into print only seven years before Villepigue’s closes, and years after Jim was dead. I would discount it, if not for it also being printed in a 1936 Massachusetts paper in 1936 and attributed to the restaurant. Why Massachusetts? Who knows, but Villepigue’s was a nationally famous restaurant.

The drink itself is nothing more than a Manhattan with orange bitters and an olive. Brooklyn cocktails just can’t seem to escape the shadow of the mighty Manhattan.

Otherwise, as far as 20th-century Brooklyn cocktail drinking was concerned, you could get a good drink at the Brooklyn branches of various Manhattan-born chains, such as Child’s and The Brass Rail. And Gage & Tollner always had a solid bar program, just as the reborn version of the chop house does today. So did long-standing institutions like Gargiulo’s in Coney Island.

For me, though, the golden age of Brooklyn cocktails didn’t begin until this century. As usual, this chapter is all tangled up with Manhattan cocktail history. It begins with Italian bartender Vincenzo Errico inventing the Red Hook cocktail at the Lower East Side speakeasy Milk & Honey in 2005. Errico was trying to created a riff on the Brooklyn cocktail that featured Italian ingredients like maraschino liqueur and Punt e Mes.

This riff so impressed other young cocktail bartenders that they all created their own Manhattan/Brooklyn cocktail spins within a few short years in the late aughts, each of them named after a Brooklyn neighborhood. And so, today, we have the Greenpoint, Bushwick, Bensonhurst, Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens, Bay Ridge and more. Nearly all are made with a base of rye and vermouth. The differences are in the details.

But, as with Grohusko, these drinks honoring Brooklyn were created by bartenders who worked in Manhattan. Many lived in Brooklyn, but they didn’t work there.

As far as I can tell, only three Neighborhood Cocktails named after Brooklyn nabes were actually invented in Brooklyn: The Slope created by Julie Reiner at Clover Club; the Bay Ridge, dreamed up by Tom Macy, also at Clover Club; and the Brooklyn Heights invented by Maxwell Britten at Jack the Horse.

The cocktail named after specific parts of Brooklyn have been much more successful than any cocktail just named plain old Brooklyn.

Sheepshead Bay Cocktail

Villlepigues, Brooklyn, 1934

2 ounces rye whiskey

1 ounce sweet vermouth

2 dashes orange bitters

Combine ingredients in a mixing glass. Shake with ice for 10 seconds. Strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Garnish with an olive.

Odds and Ends…

The team behind The Dead Rabbit bar in Manhattan is now in the travel business. They are conducting tours of Ireland, featuring the artisans, distillers and culinary talents of the island nation. The week-long itineraries are curated by Mark McLaughlin, TDR’s Galway-based Director of Irish Whiskey. The 2024 tour is currently underway. Tickets for the 2025 tour of Belfast and Dublin will go live soon… Dutch Kills in Long Island City, Queens, has a new head bartender, Jason Kilgore. Kilgore has previously worked at Dear Irving and Basik. Also, a new cocktail menu will drop at Dutch Kills this week… Speaking of Dear Irving, the third location of the Manhattan cocktail bar mini-chain opened last week. It is called Dear Irving on Broadway and is located on the fifth floor of 1717C Broadway, between 54th and 55th Streets. With Dear Irving on Hudson at 40th Street, the bar group now has Times Square surrounded… Raines Law Room at The William will celebrate 10 years in business next week… Film Forum is currently screening a George Stevens series through Oct. 19, featuring every film made by the mid-20th-century film director… Veteran drinks journalist Kara Newman is the guest on the most recent episode of The Philip Duff Show podcast… Bar Convent Berlin, the annual drinks confab, will run through Oct. 16… Bartender Tony Milici, formerly of Rolo’s in Ridgewood, who was briefly at Hellbender Nightime Cafe and was most recently behind the stick at Mister Paradise, has taken a position at the new Experimental Cocktail Club in Manhattan… OG cocktail writer Eric Felton has a Substack newsletter now. Give him a follow!… Luxardo, The Italian spirits producer, has introduced a line of bitters. There are five flavors: Cherry, Coffee, Chamomile, Orange and Rhubarb. They are currently available nationally at $20 for a 200 ml bottle… After 18 years as an intrinsic part of William Grant and Sons, one of the largest liquor conglomerates in the world, Charlotte Voisey, one of the most noted and visible brand ambassadors of the cocktail revival of the last 20 years, has decided to move on. We wish her luck with her next adventure!

Brooklyn!! I want a shore dinner!!

Although Robert knows a place where you can get a “real” Brooklyn Cocktail! Right @robertsimonson?