In Search of City Chicken

Searching for Signs of a Forgotten Depression-Era, Rust-Belt Dish.

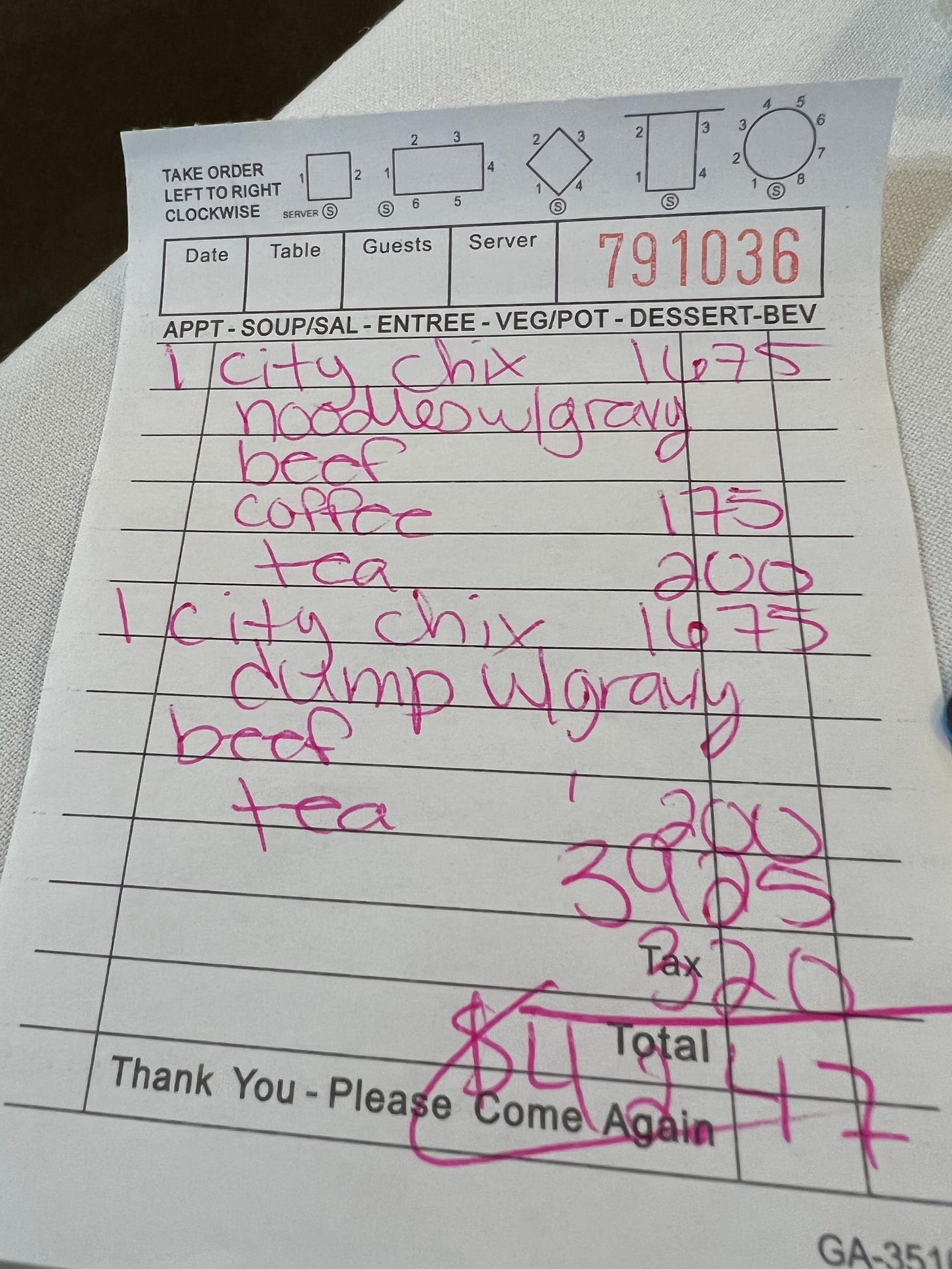

Earlier this year, I was doing research into Hot Pie, a regional variation on pizza specific to Binghamton, New York. I noticed that nearly every Binghamton restaurant that advertised in the 1930s, ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s always boasted of making three dishes: Hot Pie, Spiedies, and City Chicken.

Spiedies I knew. Anyone who’s ever visited Binghamton even once is aware of the marinated meat sandwiches. Hot Pie I was coming to know. But what was City Chicken? I pictured a chicken with a top hat, bow tie and a monocle strutting down the boulevard.

A little digging quickly revealed the central crazy fact about City Chicken—that is, it’s not chicken. It’s never chicken. It’s usually pork, sometimes veal, sometimes both, but never chicken. The second crazy fact—one that will blow the mind of anyone who has been to the butcher or supermarket in the last thirty years—is that City Chicken came to be because pork and veal were once much cheaper than chicken. City dwellers longed for chicken, that fancy delicious bird that only farmers got to eat, the lucky devils. But the elusive fowl were raised in the country, and were hard to obtain in the city and expensive when found. So city mice fashioned a pork-veal dish as a sort of mock chicken.

That was the sort of upside-down bizarro universe our ancestors once lived in.

The dish itself is sort of a cross between a spiedie and weinerschnitzel. You take cubes of seasoned pork or veal, season them and put them on skewers. You dip the skewers in flour, then eggs, then breadcrumbs and then fry them until brown. You then finish off the cooking in the oven at a low heat over a long period of time, often hours, until the meal is tender and nearly falls off the skewer. The “chicken” moniker also applied because people typically ate directly from these skewers, in the manner of eating a drumstick. City Chicken is hearty stick-to-your-ribs stuff, just the sort of thing to fill up a large Depression-era family on a limited budget.

I had never heard of City Chicken because I didn’t grow up in a City Chicken city. It was a delicacy prepared in Rust Belt towns, primarily Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Buffalo, Erie, Scranton and Binghamton. But I knew people from City Chicken cities. And boy did they remember City Chicken!

The eyes of Robin Robinson, a whiskey author and expert I know, went wide when I brought up the topic. Robinson grew up in Pittsburgh. “It was always a home thing because of the ‘shame’ of it,” he told me. “Not real chicken. Working-class food. We always had it on a weekday. Saturdays were less formal and Sundays brought out the real meats.”

Michael Ruhlman, a food writer from Cleveland, remembers his grandmother making City Chicken for him. “I loved it when she did,” he said. “I had no idea what it was. I thought it was chicken.” He’s pretty sure his grandma used pork shoulder, and still recalls the taste of the dish. “They had this savory, fatty deliciousness that I’ve longed for ever since. During the pandemic, I said, ‘I gotta make City Chicken.’”

As there is no place to eat the dish in New York City, we set out to find City Chicken elsewhere. And here’s what we discovered: City Chicken is hard to find. Unlike other regional specialties, it’s mainly a home dish. Years ago, many restaurants served it. But few do today. And those who do, like the nearly-100-year-old Pittsburgh Inn in Erie, PA, make it a special, served one night a week. Moreover, the pandemic was very bad for City Chicken. Old places which used to regularly serve City Chicken, like Sokolowski’s University Inn, outside Cleveland, and Sharky’s Bar & Grill, an institution in Binghamton, shut down for good. Another Binghamton restaurant that served the dish, Czech Please, also closed.

Those closures made it very hard to find the dish in Binghamton, once a City Chicken stronghold. But, after much searching, we did find it, not at a restaurant but at a longstanding deli called Chenago Bridge Red & White. They not only made and sold City Chicken, but had various unusual flavors, like Buffalo, BBQ, Honey Mustard and Bourbon Street. We bought a package, took it home, heated it up and ate it. We honestly had low expectations, but it was delicious.

Our appetite whetted, we now wanted to experience City Chicken in a restaurant setting. It took some doing, and a lot of phone calls, but we found a few places that still had City Chicken on the menu. Armed with this intel, we planned a course of action over the long Labor Day weekend.

The City Chicken tour began with lunch at Marie’s in Cleveland. Marie’s stands on a lonely corner as a solitary bastion of what was once a thriving Croatian community. It opened in 1982, but looks like it’s been there since 1932. When we walked in, we weren’t sure the restaurant was open. No one was there and none of the tables were set. Soon the lone waitress appeared. She seated us at a table against the wall in a spacious, high-ceilinged room empty except for two other diners. Marie’s only sets a table when a diner shows up.

All was silent except for a radio playing in the distance. Marie’s is one of those increasingly rare old-school restaurants that doesn’t believe in any noise beyond conversation. I know of only a few that are left and I treasure them. It was as silent as a funeral parlor. To eat a meal in peace in a wonderful thing.

We had called ahead and notified Marie’s that we’d be coming in for City Chicken. “You should know that we make City Chicken Croatian style,” the waitress warned us. “It’s not battered and deep fried. We grill it. Some people get upset.”

We were a little upset. Were we going to to get actual City Chicken? “It better not be chicken,” worried Mary Kate. “It better be pork.” Indeed, that’s one thing I can state after all my City Chicken research. City Chicken, to be true City Chicken, must never be chicken.

Our suspicions were unfounded. It was pork, six chunks per skewer. And while grilled—and thus unorthodox—it was moist, tender and delicious. Better was what surrounded it—toothsome homemade potato dumplings the size of large gnocchi, covered in brown gravy.

We asked the waitress if there were any other restaurants in Cleveland that served City Chicken. She turned to an old man wearing a porkpie hat at a corner table. Though the man professed to beging a regular at Marie’s, and testified that everything they made was great, he said, “City Chicken? I don’t know that I’ve ever had City Chicken.”

From Cleveland, we drove to Polish Village Café in Detroit for dinner. It was to be a Double-City-Chicken day. We had called ahead to Polish Village as well and taken the unheard of precaution of having them set aside two orders of City Chicken. When we had called earlier, they had told us they had actually run out of City Chicken an hour before closing. That made us nervous.

We had reason to nervous. Polish Village is a crazily popular place. It is located in the municipality of Hamtramck, a small city within the city of Detroit. It’s on a side street which is lined with cars, all belonging to people dining at the restaurant. We arrived at 4:30 and the basement space was already packed, mainly with large parties. Who eats dinner in the middle of a Saturday afternoon?

It was hot as hell inside, as the air-conditioning had broken, and we were seated by the open kitchen. We ordered the City Chicken from our young Polish waitress, who told us it was one of the three most popular dishes on the menu. As there was a $50 minimum to use a credit card, and prices were low, we piled on additional items, including pierogis, pickle soup and Polish beers.

The City Chicken at Polish Village was a completely different affair from Marie’s. it was made of densely flavored, dark pork—so dark we thought it was beef at first. It had been cooking so long it all but fell off the skewers. It was gamey, in a good way, if pork can be gamey. Mary Kate thought it tasted almost smoked, as if something had made pulled pork and then pressed it into a solid form.

As we had at Marie’s, we asked for a to-go box to take much of the food home. Anyone who can finish a City Chicken dinner in one sitting has an impressive appetite. No wonder they loved this dish during the Depression.

Mary Kate learned from a woman at Polish Village that Polonia, another Polish restaurant just down the street, also might have City Chicken on the menu. So we walked over. It was a lighter, brighter place. Whereas Polish Village felt like the rec room at an Elks Lodge, Polonia looked like any old restaurant, just one with a huge Polish mural on the back wall.

We ordered a City Chicken to go, as it is not humanly possibly to eat three City Chicken meals in one day. Polonia’s version was quite similar to Polish Village’s except for the cut of meat, with was much lighter. That made all the difference in the flavor. It may have been my favorite.

All the rest of that day, as we chatted with locals at our hotel and at bars, it was clear we were in a city that had not forgotten City Chicken. Everyone knew what we talking about. A smile would flit across their faces when I mentioned the dish. Unlike Pittsburgh and Cleveland, Detroit’s memory of the dish was still strong. One woman, who had been fed City Chicken as a kid, said she had started feeding it to her young children.

So, we managed to experience City Chicken as a restaurant meal. Now, it was time to experience it the way most people did—at home. I combed through my cookbook collection. I own a lot of old cookbooks, standbys of the 1950s and ‘60s like Betty Crocker, Good Housekeeping and the New York Times Cook Book. Not a single one contained a recipe for City Chicken. It was bizarre. Perhaps, like Robinson had pointed out, it was a shame thing. A respectable mass-market cookbook wasn’t going to sully its pages with City Chicken.

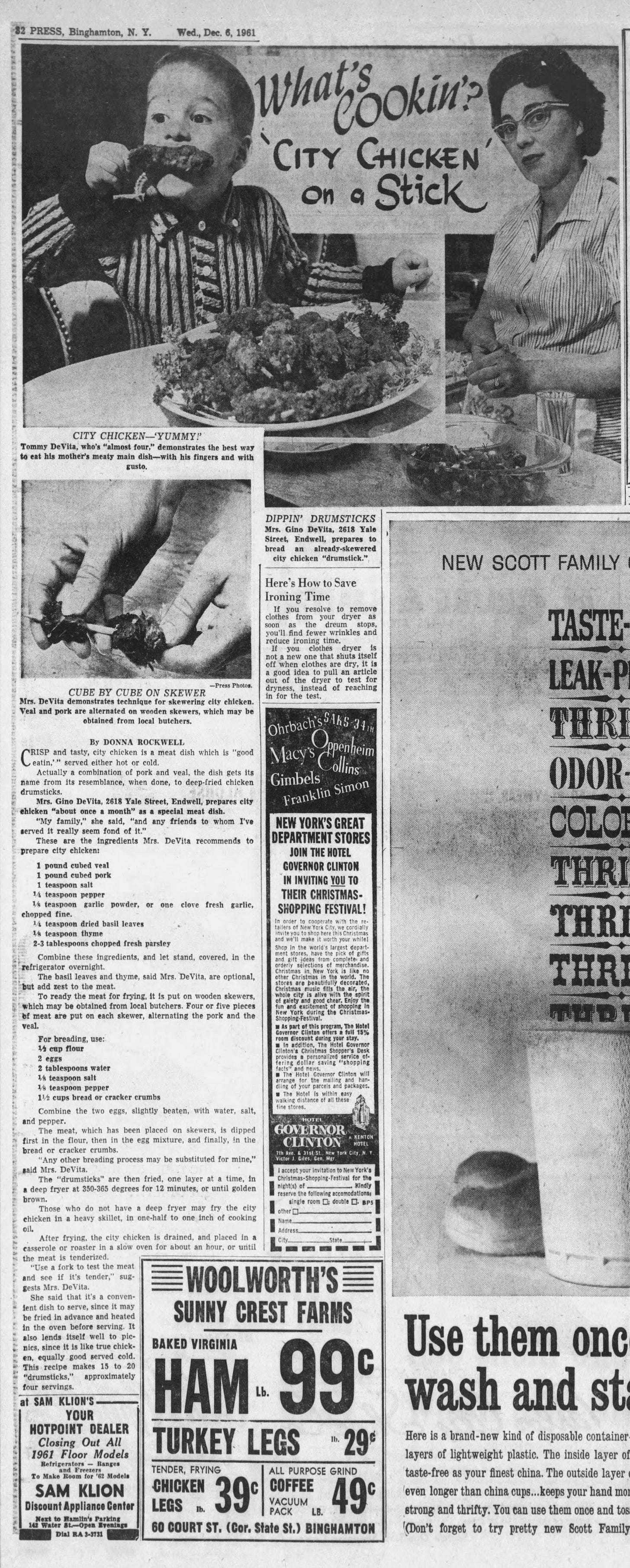

So I turned to the newspaper archives on the Internet. City Chicken was popular enough in the mid-20th century that recipes for it appeared often in the Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Binghamton and Detroit papers. I found what I was looking for in a 1961 article in the Binghamton Press titled “What’s Cookin’? City Chicken on a Stick.” It had a picture of a hungry kid manically devouring a skewer of City Chicken and a supremely confident housewife named “Mrs. Gino DeVita.”

The recipe printed was DeVita’s and it had everything I was looking for, including alternating cubes of pork and veal on each skewer, which struck me as key to created a sublime City Chicken. Also important, as I saw it, was that, after being breaded, the meat was first fried and then baked for a very long time at a relatively low temperature. The frying gets you the nicely browned outside; the slow oven baking renders the meat tender.

The recipe worked out perfectly. And I have to say, as a rookie City Chicken maker, I knocked it out of the park first time at bat.

And, just as had many Rust Belt parents before us, we fed it to our kids. Mary Kate invited her son Richard over. He loved the stuff. And he ate it just like the kid in the 1961 newspaper photo did, picking up the skewer like it was a drumstick and sinking his teeth into it.

The recipe is in the newspaper clipping pictured above. I won’t reprint it because I followed it to the letter with no changes. Try it. You might like it. As Robin Robinson said to me, “It’s about time City Chicken got some love.”

Odds and Ends…

The official launch event for my new book Modern Cocktail Classics will be held at the Manhattan bar Porchlight on Monday, October 3, from 6 to 8 p.m. A $55 ticket will get you a signed copy of the book and drinks; $35 will get you just drinks. But what drinks! Guest bartending will be authors of four of the drinks in the book: Don Lee (Benton’s Old-Fashioned), Joaquin Simo (Kingston Negroni), Franky Marshall (Mr. Brown) and Meaghan Dorman (Wildest Redhead). Look for a link to the event to appear on the Porchlight event sometime today… my book, 3-Ingredient Cocktails, published on this day in 2017, turns five years old today. So celebrate five years with three ingredients tonight!… I wrote something about the dawning of a new ‘tini age for the New York Times… I also wrote something about how some bars are now making their Ramos Gin Fizzes in a blender, for Vinepair… Jeremy’s, the new Upper East Side cocktail bar from the owners of Schaller & Weber, which was to have opened on Sept. 21, will now open on Sept. 30… Trixie’s in Ephraim, Wisconsin, may have the best food in Door County… In other Door County news, Egg Harbor is now home to Daughters & Co., a resource for fine wine and spirits. It is run by Ryan Ibsen… José Andrés has opened Nubeluz, a rooftop bar inside the Ritz-Carlton New York in Nomad at 25 W. 28th Street. The cocktail program is led by Miguel Lancha, the creative force behind the acclaimed barmini in D.C. A sample cocktail is the Foggy Hill made with Del Maguey Vida mezcal, Yzaguirre 1884 Gran Reserva vermouth, Cynar, Aperol and a “orange-thyme aromatic cloud.”

Great story, thanks! Thanks especially for the newspaper clipping, which jibes with who my grandma likely made it. Yours looks perfect! Good luck with the book!

Nice article and great sleuthing. I also grew up having this several times a month (northeast Ohio) but never on Sunday as it wasn’t deemed fancy enough. I still make it several times a year in the cold months.