On Eating and Reading, Separately and Together

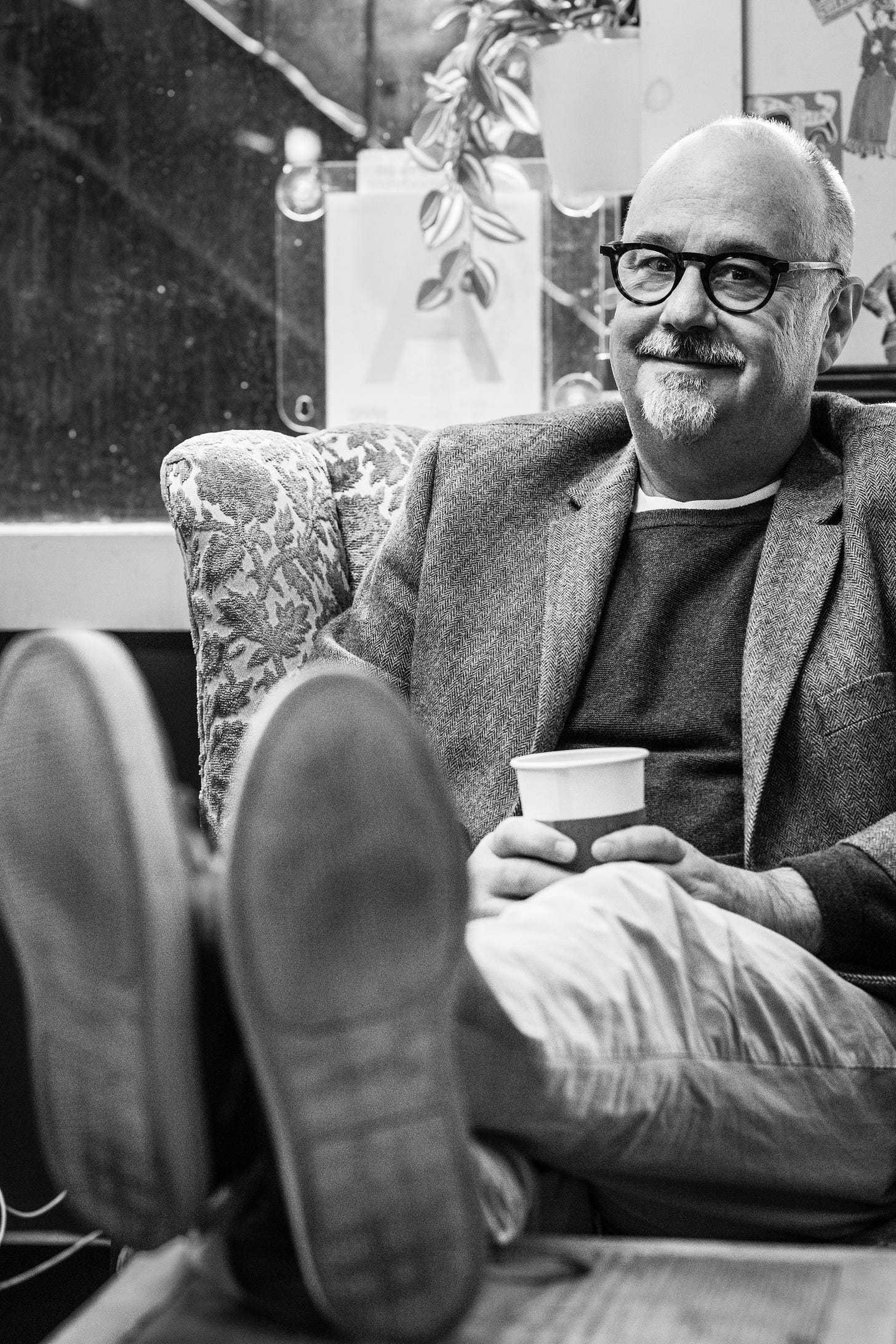

An Excerpt from Dwight Garner's New Book, "The Upstairs Delicatessen."

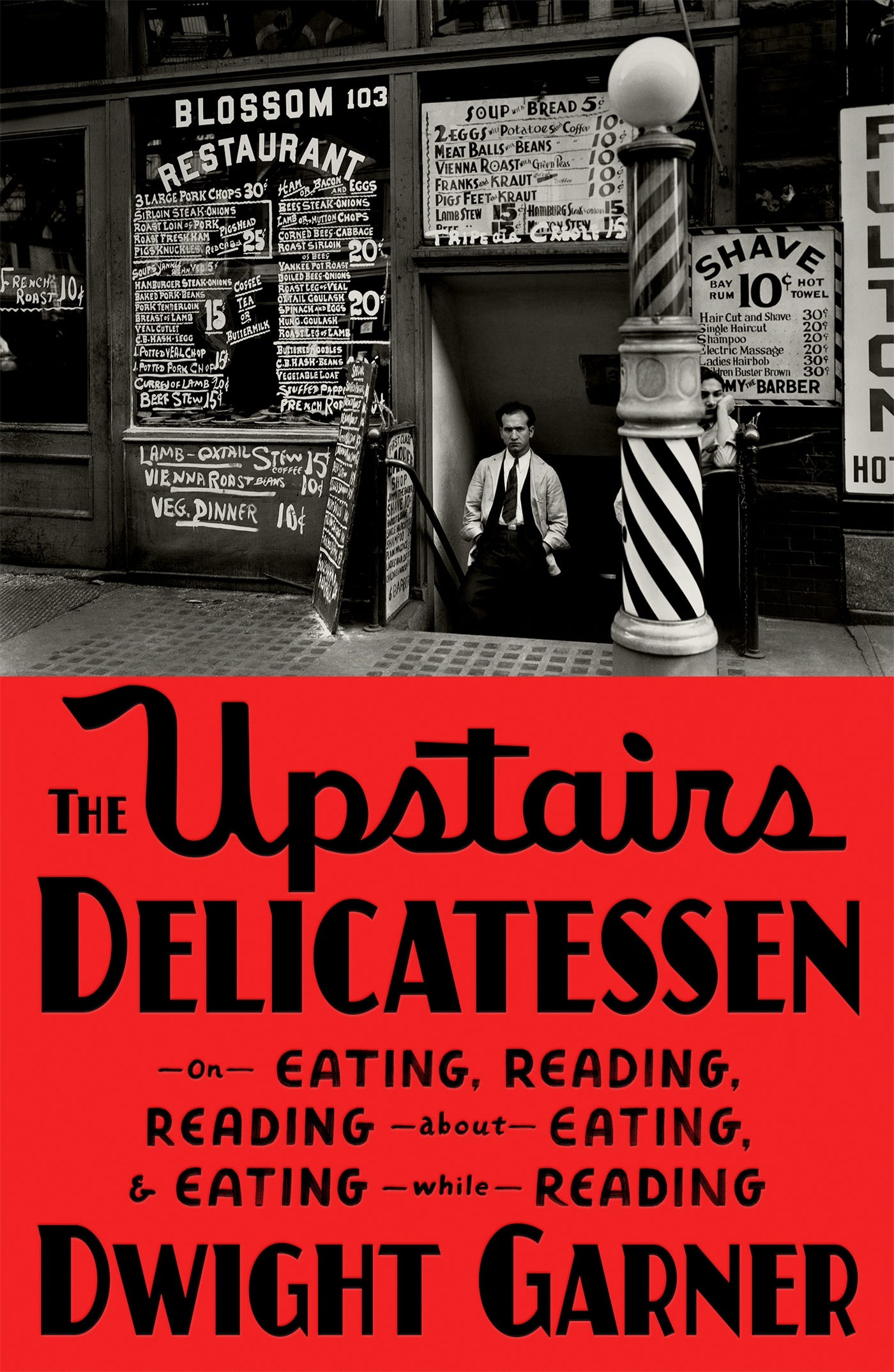

I am—as I imagine most writers are—with Dwight Garner in his enthusiasm for both eating and reading. His delightful new book, The Upstairs Delicatessen, bears the even more delightful subtitle “On Eating, Reading, Reading about Eating, & Eating While Reading.” Which should leave you with few questions as to what the breezy, highly entertaining volume is about.

From an early age, Garner was inclined to find his greatest joy in mashing up his twin passions. After school, he would lay out several newspapers and books on the living room floor, fortify himself with snacks from the kitchen, and happily erase a few hours. Since becoming the book critic at The New York Times, he seems to have made a practice of extracting what writers of all stripe—from novelists to memoirists to poets to critics—had to say about food and drink and then filed the information away in a particular file in his brain. All those literary morsels are compiled here, arranged into a daily chronology that takes you from breakfast to dinner.

Along the way, he drops a library’s worth of names, including James Baldwin, Jim Harrison, Christopher Hitchens, Anthony Bourdain, Samuel Beckett, Robert Christgau, John Cheever, Cyril Connolly, Seymour Krim (from whom he nicked the title of the book), Dr. Samuel Johnson, William Faulkner, Bruce Jay Friedman, Iris Murdoch, Jonathan Gold, Nora Ephron, Virginia Woolf, Denis Johnson, A.J. Liebling, Norman Mailer, Frank McCourt, Cormac McCarthy, George Orwell, Dawn Powell, Sam Shepard, Salman Rushdie, William Thackeray, Alice Walker, Percy Bysshe Shelly, Eudora Welty and Edith Wharton. (In the excerpt printed below, he managed to city 14 different writers, and one editor, in six brief paragraphs.)

About each, you learn a little about what they, or the characters they created, liked to eat and drink; or how they prepared their food and drink; or what they thought about food and drink. Friedman said the way to learn how to cook was “to pick up one tip from every person you date.” Harrison, who liked chicken thighs, thought “chicken breasts are the moral equivalent of a TV commercial.” Murdoch wrote that “one of the secrets of a happy life is continuous small treats.” I completely agree with her on that.

The ever-cutting Dr. Johnson wrote, “A cucumber should be well sliced, and dressed with salt and pepper, and then thrown out, as good for nothing.” And the ever-sage Liebling declared, “A good meal in troubled times is always that much salvaged from disaster.” Shelley was a confirmed vegetarian until confronted with a plate of bacon. After taking one bite, he called out, “Bring more bacon!” Woolf noted writers’ tendency to not mention food in their fiction, which she found odd, “as if soup and salmon and ducklings were of no importance whatsoever.”

Of course, the chapter titled “Drinking” most peaked my interest, the several paragraphs about Martinis in particular. Garner and I diverge on the subject of Martinis. I like them with gin, with considerable vermouth, stirred and with a lemon twist. He prefers them shaken, with little vermouth and sometimes vodka-based. But, as with the best writers and journalists who dabble in cocktail writing (Kingsley Amis, Bernard DeVoto, etc.), I like the way he expresses his opinions.

He also includes a certain off-color anecdote about the English drama critic Kenneth Tynan’s unorthodox, one-off method of taking his Martini. I’m familiar with the story, which is taken from his diaries, and admit it is funny. But because I am overprotective of Tynan, who is one of my literary heroes, I encourage the reader to seek out Tynan’s criticism and profiles before judging his perverse sexual peccadilloes too harshly.

(Excerpt printed with the permission of FSG.)

I make a martini, Gordon’s or Barr Hill, every night at seven with, in my mind at least, a matador’s formality. I use dense, square ice cubes. Like the pop of a cork exiting a bottle, a martini’s being shaken is one of civilization’s indispensable sounds. The martini is the only American invention, Mencken wrote, as perfect as a sonnet.

I like my martinis shaken rather than stirred because they seem colder and because the ice crystals that swim briefly on the surface are ethereal. I also like mine extremely dry. I was pleased to read, in the 2018 Times obituary of Tommy Rowles, the longtime bartender at Bemelmans Bar at the Carlyle hotel, that his secret was to omit vermouth entirely. “A bottle of vermouth,” he said, “you should just open it and look at it.” Modern cocktail orthodoxy is not kind to me, or to Tommy. Stirring, these days, is in, and vermouth is poured with a heavy hand. T.S. Eliot would not have minded. He was a vermouth man, so much so that he named one of his cats Noilly Prat, after his favorite brand. When I do add vermouth, I apply Hemingway’s formula, 15:1, in honor of Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, who liked gin to outnumber vermouth in the same ratio he wanted to outnumber opponents in battle. The toast I make, with whoever is present, is usually the one I learned from the late Caroline Herron, a former editor at the Times Book Review: “To the confusion of our enemies.” The toast Jack Nicholson makes in Easy Rider—”To old D.H. Lawrence”—isn’t bad, either.

“The world and its martinis are mine!” Patricia Highsmith exclaimed in her diaries. Martinis inspire this sort of enthusiasm. Frederick Seidel, in his poem “At Gracie Mansion,” refers to an ice-cold martini as a “see-through on a stem.” The poet Richard Wilbur liked to add “fennel juice and foliage” to his. I’d like to be like Eloise, in the children’s book by Kay Thompson, and keep a bottle of gin in my bedroom. If you want to go broke quickly rather than slowly, drink your martinis outside the house.

Occasionally I’ll mix a vodka martini, recalling that Langston Hughes appeared in a Smirnoff advertisement. Vodka martinis flush out the snobs, who don’t consider them Martinis at all. Roger Angell, whose New Yorker essay “Dry Martini” is the best thing I’ve read on the subject, admitted that he and his wife moved from gin to vodka because vodka was “less argumentative.” The best paean to the vodka martini appears in Lawrence Osborne’s amazing book The Wet and the Dry, which is about trying to get a drink in countries where to do so is against the law. Osborne decides that, with its olive, his vodka martini tastes like “cold seawater at the bottom of an oyster.”

Don’t get all excited, as Kenneth Tynan, and try to take your vodka martini rectally. Tynan had read, in Alan Watts’s autobiography, that this was a good idea. Tynan had his girlfriend inject the contents of a large wineglass of vodka, via an enema tube, into his rectum. “Within ten minutes the agony is indescribable,” he wrote in his diary. His anus became “tightly compressed” and blood seeped from it. It took three days for the pain to abate. “Oh, the perils of hedonism!” he wrote.

I make my first drink on the late side because I like it too much. I also want to prolong the anticipation. Alcohol is, as Benjamin Franklin noted, constant proof that God loves us. I drink more than most people less than some. I don’t have an especially big tank; my tolerance is not Homeric. But almost nightly I drink two martinis and, with dinner, a glass or two of wine, without negative effects in the morning. If I have that third glass of wine, my morning at the desk becomes an afternoon at the desk.

OTHER BOOKS I’VE READ LATELY:

*The Dish, food writer Andrew Friedman’s hyper-focused book on everyone who makes a contribution to the a single dish in a single restaurant.

*Between the Lines, my brother Eric Simonson’s memoir on his return to the stage as an actor, and the early years he spent in Chicago during that city’s late-20th-century theater boom.

*Dusty Booze, liquor writer Aaron Goldfarb’s study of the recent craze for vintage spirits and the people who pursue them.

*That’s So New York!, New York Times editor Dan Saltzstein’s compendium of ur-New York essays and anecdotes.

*Juke Joints, Jazz Clubs and Juice, food historian Toni Tipton-Martin’s look at the contributions of the Black chefs, mixologists and writers to the drinking culture of the United States over the centuries.

What have you read lately? Leave a comment below.

Hard to get past the Tynan part, you are right.

I prefer my Martini’s to be taken orally myself.

Great book. Definitely enjoyed.