The Bitter Truth

To Get Some Answers About Angostura Bitters, the Cocktail World's Most Mysterious Product, I Went to the Source in Trinidad.

How can a product be ubiquitous and mysterious at the same time?

Well, it can be done. Look at Heinz ketchup. It’s in every restaurant, every home. But what do any of us know about how it’s made or what it is exactly about the formula that makes it forever the king of the condiment market? KFC has been talking about its 11 herbs and spices forever, but no one knows what they are. There’s a can of WD-40 in most every garage or under every kitchen sink in the nation. But can anyone says what’s in that stuff that makes your door hinges stop squeaking?

In the liquor world, the greatest mystery product, arguably, is Angostura bitters.

You need it to make an Old-Fashioned and Manhattan and many other cocktails. The brown bottle with the yellow cap and oversized paper label is instantly recognizable and stocked in grocery and liquor stores the world over. Few products have benefited more from the worldwide cocktail revival of the past quarter century.

And yet, in 18 years of covering the cocktail beat as a reporter, I have found contacting Angostura akin to navigating the Vatican. I don’t know where to start and I rarely get anywhere. In the few instances where I actually reached somebody connected with the company, they seemed genuinely flummoxed by the idea that a reporter would ask them about their business. Anyway, they never had the answers to the questions I asked—or, perhaps more likely, they didn’t want to answer.

So, when I recently received an invitation to visit the Angostura facilities in Trinidad, I could hardly say no. Angostura was celebrating its 200th year in business and, for once, wanted some press attention. Here was my chance to finally fill in some of the many blanks in the Angostura story.

The Good Doctor

As befits a product like no other, Angostura Bitters has a history like no other.

Dr. Johann Gottlieb Benjamin Siegert, a native of Germany, moved to Venezuela in 1820, settling in the town of Angustura along a narrow stretch of the Orinoco River. (Angostura translates as “narrow.” So you are drinking Narrow Bitters.) He was a surgeon in the army of Simón Bolívar, the military leader and statesman who led Venezuela to independence from Spain. By 1824, he had developed his own brand of bitters, which was used to aid the various stomach ailments of the Bolívar soldiers. The mixture became popular.

The bitters were named after the town, not Angostura bark, as is commonly believed. By 1846, the town Angostura was renamed Ciudad Bolivar. So, technically, Angostura Bitters are named after a place that no longer exists.

As early as 1830, Angostura Bitters were exported to Trinidad and England. The good doctor died in 1870. After that, his sons Carlos, Alfredo and Luis took over. Seeing the situation in Venezuela had grown quite volatile, they moved the company in 1875 to Trinidad, which had long been an important port of call for the company, and where they enjoyed the protection of the British monarchy. (The family’s connection to the island country was strong. The doctor actually had a daughter named Trinidad, who lived from 1835 to 1864.)

A long, two-story building was acquired on George Street in Port of Spain. This was the Angostura headquarters for many decades. The building burned down ten years ago. Angostura is now based in an sprawling industrial plant to the southeast of the city.

By the late 19th century, Angostura had found its way into many cocktails as a flavoring agent. It competed for that market with many other bitters brands, all of which had begun life as medicinal products. By the time Prohibition ended in 1933, however, the bitters field had been swept clear of competitors and Angostura stood virtually alone.

In 1937, Robert Siegert, a chemist, decided to create a range of rums, expanded Angostura’s output. Prior to that, Angostura bought their alcohol from local rum producers.

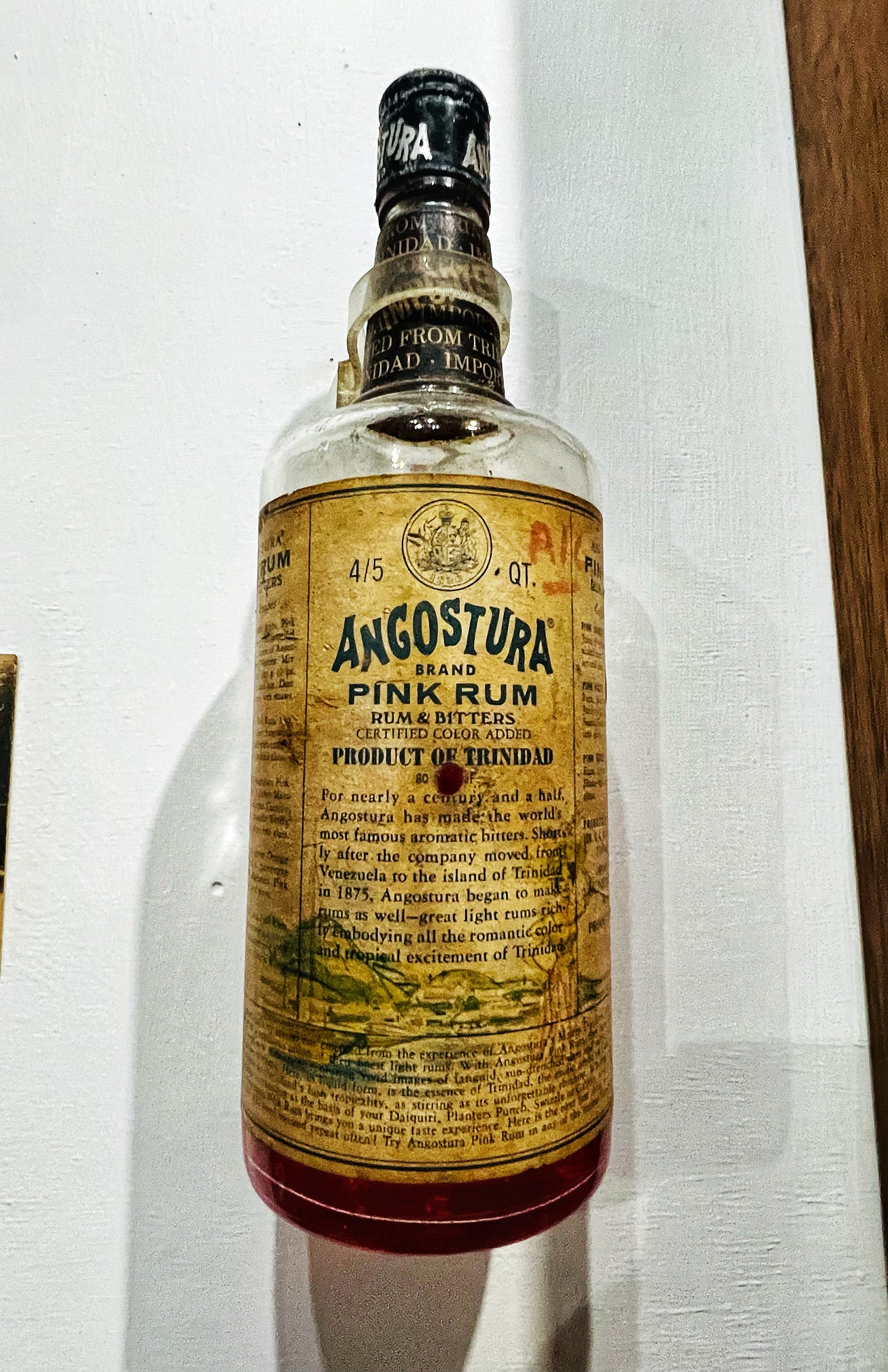

Angostura has produced many other products over the years, including Pink Rum, which is just like Pink Gin (gin with bitters), only with rum; a bottled Rum Punch; Caribbean Club Limbo Drummer Rum, which came in a distinctive bottle shaped like a Trinidadian drummer in a colorful blouse and straw hat, and stopped production when Covid came along (full bottles are now collector items).

It also bought out other competing rum brands, like the various Forres Park rums, made by Fernandes Distillers, in 1970. (The Fernandes distillery used to stand directly opposite Angostura.) Angostura still sells brands that used to be Fernandes brands. Another once-prominent Trinidadian rum company and Angostura rival was Caroni. It and its rum stocks were sold by the government to Angostura in 1999. Caroni no longer exists. In fact, Angostura is the only distillery left in Trinidad.

In 1958, the Trinidadian government fended off a hostile takeover by a Canadian business named Douglas H. Bradley, by acquiring the company itself. Bradley was president of Angostura-Wupperman, a company that had a distribution franchise for the product. (Fun fact: Frank Morgan, who played the title role in The Wizard of Oz, was born Francis Wupperman, and was a vice-president and stockholder in Angostura-Wupperman until his death in 1949. This all brings a new meaning to “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”)

The last Siegert to be involved in the business retired in 1990.

In 1997, CL Financial, one of the largest privately held corporations in the Caribbean, purchased Angostura and Trinidad Distillers. Angostura was one of many liquor companies the corporate giant would acquire in the decade to come. That marriage would not end well, as we will learn below.

The Chairman

For my purposes, there were two main attractions in journeying to Trinidad: a meeting with the company’s chairman; and a tour of the distillery.

The chairman of Angostura is Terrence Bharath S.C., a barrister by trade. S.C. stands for “senior counsel,” which is a class of lawyer among current and former member countries of the British Commonwealth. They were once called “King’s counsel.” They are also known as “Silks.”

Bharath is a small-framed man with close-cropped hair. The day of our meeting, he was dressed in an expensive, tailored blue suit with the windowpane-plaid pattern. He spoke with a calmly confident cadence of one has spent many years in the courtroom, and emanated the quietly intense air of a man whose every waking minute is spoken for. He said he slept four hours a night, worked six days a week and trafficked in “very complex litigation” of the commercial and criminal kind.

(One journalist in our company was something of a watch expert, having written her share of lifestyle journalism. By the end of the meeting, she had determined that the large watch the chairman was wearing, one that glinted with light every time he shot his cuffs, was worth $30,000.)

Bharath has worked with Angostura since 2016, when he was made director. He was asked by the majority shareholders of Angostura to be the company’s chairman in 2018 and has been ever since.

What does being the chairman of Angostura entail?

“I chair the board, so I come in for meetings,” he said, “and my role really goes a little bit beyond that, because I think the company has become pretty dependent on my advice… And then, of course, my role is to pilot the company in the right direction. And at the end of the day, I'm responsible if something happens in Angostura that's beneficial to Angostura or non-beneficial.”

The meeting lasted for more than an hour. I was invited to lob the first question. So, I asked, who runs Angostura anyway? Given the company’s complex business history in recent decades, I thought it was a fair query.

“It is a publicly traded company, just like in the U.S.,” he began, “and the shareholders, I would say, they may be teachers, they may be retired civil servants. And then there's the state. And you know, Angostura has a very rich history. So we were, at one stage, owned by a conglomerate, which still exists, called CL Financial. The CL Financial conglomerate was extremely large in the fabric of Trinidad and Tobago; they traverse methanol, insurance, seaports, rums.”

For many years, according to a 2024 article in the Trinidad and Tobago Guardian, CL Financial and its subsidiary Clico were Angostura's largest shareholders, owning 44.96 per cent and 32.53 per cent of the rum and bitters producer respectively.

“They were all in,” said Bharath. “They had their fingers in everything. And in 2009, CL Financial collapsed, and because it would have caused the economy to be very badly affected, the government pumped, I think it was $29 billion into CL Financial to try and keep it afloat.”

As part of the bailout, the Trinidad government gained a majority number of seats on the CL Financial board of directors. After a decade of turmoil, it was decided that CL Financial would be liquified.

“With that 2009 catastrophe, quite a bit of monies went missing from Angostura,” continued Bharath, “and they became delisted from the stock exchange and recovered over the years leading up to now. So to answer your question, and sorry to be so long-winded, it's a melting pot of people.”

Earlier this year, the liquidators of the CL Financial group rejected a claim by Angostura Holdings Ltd to be repaid a debt of $984.55 million. That fight continues today.

So, does all of the above make it clearer to me who really controls Angostura? Not really. But I will say this. It troubles me that a product that brings so much joy to so many millions, as a critical component to their nightly cocktail, is subjected to the shifting winds of corporate and governmental machinations.

Still, there were other things to learn! For instance, 30% of Angostura’s revenue is bitters. That surprised me. I expected the number would be much more. But 30% is a lot.

According to 2023 revenue figures, Angostura moved 614 million dollars in rum, and 298 million in bitters. The company also sells bulk rum.

The bitters is primarily exported; Trinidad and Tobago can only consume so much, after all. The United States, Canada and Mexico are the company’s biggest markets. Europe is a much smaller market. They recently entered the Chinese market.

The bitters are in 170 countries, and Angostura occupies a whopping 85% of the bitters market.

Social Butterflies

The Angostura distillery is a curious place. The visitors area is a warren of hallways and small rooms. Every space is filled with artworks by local artists that have been commissioned by the company over the decades. There are also blowups of various Angostura ads that ran in American magazines in the 1940s and ‘50s, featuring the bizarre work of cartoonist Virgil Partch. (I wrote about Partch’s work in an article for Punch.)

Before you get to the Angostura museum—which tells you the complete story of the brand through artifacts and displays—you must pass through a hall of butterflies. Thousands of colorful insects are mounted under glass. This is the life’s work of one Malcolm Barcant, who collected butterflies for fifty years beginning in 1921. In the 1970s, wanting to relocate to Florida, he put the collection up for sale. Angostura bought it in 1974. It’s been on display there ever since.

Queen Elizabeth II saw these butterflies during a visit in 1985, when she commemorated an extension to the Angostura distillery.

The Secret Chamber

The Blending Room is the beating heart of Angustura brand mythology. It is here that the bitters are made. And it is the only room in the complex where photographs are not allowed.

The Blending Room is not a particularly impressive sight. It’s a mid-sized, rectangular room occupied by a large red grinding machine and several silver metal tanks that reach up roughly twenty feet to the ceiling. Perched above the grinder is a small office, about halfway up the wall, with all of its windows covered. It looks like the sort of office a supervisor would occupy at a factory.

Angostura goes to great lengths to make sure the formula for its bitters is never stolen or copied. There are circles within circles of secrecy. According to the tour guide who led us through the room, only five people know the bitters recipe. They are called Manufacturers, and nobody among the rest of the plant’s staff knows exactly who they are. It is they who prepare the botanicals for the grinder. They do this work in the elevated, shuttered room. When traveling, the Manufacturers are not allowed to be in the same plane, as a precaution.

[Editorial note: As with any information communicated by liquor companies to the press, I have no way of knowing if all, or any, of this is true.]

The botanicals used in the bitters arrive to Port of Spain in coded parcels. But you won’t find any sack or barrel on a Port of Spain pier labeled “Cloves: property of Angostura.” The ingredients are identified by a numbered code. Each botanical has a number and those numbers are never repeated; with each delivery, the numbers are changed.

Also, Angostura purposely imports ingredients that have nothing to do with making bitters, just to throw people off the scent.

“We're one of the few concessionaires in Trinidad that does not have to describe what's coming in when our botanicals come in,” Bharath said in the meeting. “The people who grow the botanicals for us are under a very strict relationship with us, whereby they sign a secrecy document and they're not allowed to grow for others. And so the ingredients in those bitters are very unique.”

So: secret suppliers, secret shipping methods, secret blenders.

COO Ian Forbes is not one of those secret holders. He said he prided myself in knowing very little about the production of the bitters.

“I'm not involved in it,” he Forbes. “It's all secret. I know very little about how it's all managed, because it's managed with deep secrecy, and there are few special persons that know about these things, and I would say that all I know is that they have very, very close relationships with the suppliers, and they're contractually guarded, and it's all managed to maintain a massive ignorance about how it's done. And that massive ignorance is what allows it to be so secret.”

Once the Manufacturer has measured out the botanical mix—which is called “the concoction”—the grinder starts up. The ground botanicals are lifted by a basket into a percolator, into which alcohol is run through the back. (The botanical shavings left in the grinder are collected and incinerated, lest someone filch them for analysis.) Sugar and rum are added and the mixture is allowed to sit in its tank for a minimum of three months, becoming what is called “Angostura concentrate.” When this concentrate is ready, it is mixed with twice as much water to create the bitters and bottled.

One reporter in our company asked, “How the hell does a spirit cut by twice as much water end up at 44% alcohol.” He was right. The math didn’t add up. The Angostura official could not answer; that fell under classified information.

The day I was there, one of the large tanks had just been filled with concentrate. Another had been filled the day before. There is no manufacturing schedule at Angostura. The bitters are simply made upon demand. And every drop of Angostura bitters that supplies the world is made in that little room. When pressed, one of the Angostura officials said that 1.8 million liters of bitters is produced in one calendar year.

At our meeting with Bharath, the booze reporter Dylan Ettinger asked whether, at this point, all this secrecy was necessary, or if it was simply put on for show, to add to the air of mystery surrounding Angostura.

“I think the same thing goes for Coca-Cola,” said Bharath, measuring his words with care. “I wouldn’t know how to create Coca-Cola, but you could probably come close. But I think it's still necessary for us to maintain the mystery even about the oversized label, to the mystery of what goes into these ingredients, to the mystery of the lady going into the room and mixing the botanicals, and nobody even understanding what she's mixed, and then that room is closed. I think that mystery is important, and I think the secrecy surrounding it is important. So, I believe it's what makes us unique, and I think we will continue that way. There's no reason for us to release the formula. In fact, I think if we release the formula, people will probably flock to create something similar at a much lower price. And it won't be the real McCoy. It wouldn't be the real thing.”

The Washington Island Connection

Being from Wisconsin, there was one question I had to ask Bharath. There is an old bar in Wisconsin called Nelsen’s Hall. It’s on Washington Island in Lake Michigan, just off the coast of the Door County peninsula. The bar survived Prohibition by selling Angostura Bitters as a medicinal product. It continues to sell Angostura by the shot today; if you down a shot, you can join the “Bitters Club.”

For decades, Nelsen’s Hall has boasted that it is the biggest account for Angostura Bitters in the United States. Is this true?

“I believe there's some truth to that,” Bharath said. “We've invited them.” It’s a “very important account for us. And I think she's been here at least twice.”

Queens Park Swizzle

Trinidad, as a country, is not big on historical preservation. This is perhaps because, unlike most Caribbean islands, it does not depend on tourism to drive its economy, being a nation rich in oil and gas. The overall character of Port of Spain is industrial. The city does not charmingly beckon, “Come hither, foreign visitor.” Violent crime is common. I was told numerous times that it was not safe for me to venture about without an escort. There were too many “high risk” areas. This dissuaded me—to my great disappointment—from visiting the graves of the many members of the Siegart buried in the Lapeyrouse Cemetery, or seeking out on foot the site of the Queen’s Park Hotel.

The ritzy Queen’s Park Hotel, which stood on the southern side of the Queen's Park Savannah park, was first opened in January 1895 and closed 1996. It was here that the Queen’s Park Swizzle was invented, an iced rum-and-mint drink with plenty of Angostura bitters that Trader Vic once called "the most delightful form of anesthesia given out today."

The cocktail had been fairly well forgotten when, in the first decade of the 21st century, New York bars like Milk & Honey and Dutch Kills began to bring it back.

We had Queen’s Park Swizzles at nearly every bar and restaurant we went to in Port of Spain. Some were slapdash, but some were quite smartly done. I was mainly pleased that you could order them at all. Sometimes famous cocktails are not honored by their homelands, after all. However, I was told that this is a recent phenomenon. If I had come to Trinidad just a decade ago, I wouldn’t have found a Queen’s Park Swizzle anywhere. So, thank God, and the cocktail revival, for small favors.

As for the Queen’s Park Hotel, there is a TGI Friday’s where it once stood.

Bharath said Angostura is trying to trademark the name Queen’s Park Swizzle around the world, much like Goslings rum has trademarked the Dark and Stormy.

I asked whether he had heard of another, more recently famous drink that calls for a large amount of Angostura Bitters: the Trinidad Sour. He had not.

This is a situation that must be corrected.

Burying the Lede

From a journalist’s point of view, the biggest news of Angostura’s 200th anniversary was not the anniversary itself—though reaching the two-century mark is undeniably impressive by any measure. No, it was the fact that Angostura had come up with a new bitters to mark the occasion! This was like learning that the Carthusian monks in France were introducing Chartreuse Blue. Angostura just doesn’t do line extensions of its bitters. In the whole history of the brand, there have been only two: orange bitters in 2007 and cacao bitters in 2020.

And yet, Angostura didn’t really make a big deal out of this. I thought the new bitters would be amply featured in cocktails when we reached the company’s bar room. But they were not. Then I thought the bitters would be proudly deployed in cocktails at the gala commemorating the anniversary. But they were not. I’ve rarely seen a company hide its light under a bushel better.

That’s a shame, for the anniversary bitters are quite remarkable. They are nothing like standard Angostura. Instead of warm, baking-spice notes, they are astringent and sharp, showing the effect of the added botanicals of gentian and wormwood. I have a bottle at home. I’m still not sure what to do with it, but I’m sure some ingenious bartender will come up with an answer soon.

One answer may lie at the New York bar Amor y Amargo today. Bottles of the 200th Anniversary Bitters have been very hard to come by. But Amor has them for sale for one day only, beginning at 4 p.m. According to the below advertisement, they are the only pace you can buy the bitters in New York at present.

Odds and Ends…

Did you like Gin Week? Well, then, you’re going to love Bourbon and Rye Week, a week-long editorial celebration of America’s two favorite whiskeys, complete with feature stories, interviews, historical studies and lots and lots of reviews of bourbon and rye brands.

If you make a bourbon or rye, or represent a bourbon or rye, and would like it to be one of those bottles reviewed during Bourbon and Rye Week on The Mix, here’s your chance. Send a bottle to The Mix offices by Jan. 31 and it will be featured. To get information on our mailing address contact Mary Kate at marykatemurray@me.com.

It was a big publishing week for me. Two articles I had been working on for many weeks came out. One, for Grub Street, was about the rise of the Dirty Martini in New York City. In my research for that article, I visited many new bars, including Eel Bar, Shy Shy, Bar Snack, Smithereens, Time & Tide and The Corner Store. The other—my third column for The Wall Street Journal—was about the Old-Fashioned and a bar in Pittsburgh, The Warren Bar & Burrow, that makes a particularly good one… Toby Maloney, the noted mixologist (The Violet Hour), has been named the bar director of the TY Bar at the recently reopened Four Seasons Hotel New York. The debut menu is meant as a “liquid love letter” to New York City, “tracing the city’s vibrant cocktail history from the Gilded Age’s cocktail innovations and the liberating post-Prohibition supper clubs to the cocktail renaissance of post-WWII and the unapologetic nightlife of the 80s.” Drink prices run $29-$43 (this is The Four Seasons after all)… After many, many months of deliberating, the TTB has ratified a standard definition for the American Single Malt category of whiskey. The ratification takes place Dec. 18 and the new rule takes effect Jan. 19. One element of the category is that American Single Malt needs to be made with 100% malted barley only. However, the definition allows ASM producers more latitude on certain elements of production compared to their peers in Scotland or American bourbon makers… The chili dog has returned to Hamburger American in Manhattan. It will stay on the menu through Jan. 8… The LPC of New York voted to consider the old Whitney Museum of American Art on Madison Avenue for landmark status. The striking granite-and-concrete, Brutalist-style building was designed by Breuer and Associates… Buffalo Tofu Fingers are back on the menu at Katana Kitten… For one night only, on Dec. 21, MoMA will screen the iconic video film “The Clock” in its 24-hour entirety. The movie is a montage of thousands of time reference clips taken from film and television, spliced together and synchronized to local time… After many years of being closed, Central Grocery, the iconic home of the muffuletta sandwich, has finally reopened for business. The business closed after nearly being destroyed by Hurricane Ida. Since then, you have only been able to buy the famous sandwiches at a deli next door… The Holiday Nostalgia Trains are back at the MTA for the month of December. Antique subway trains will be running on Sundays in December. You can catch the vintage trains on December 1st, 8th, 15th, 22nd and 29th. The Holiday Nostalgia Train departs from the 2nd Avenue – Houston Street on the uptown F line in lower Manhattan at: 10 a.m., 12 p.m., 2 p.m. and 4 p.m. It departs from the 96th Street – 2nd Avenue on the Q line at: 11 a.m, 1 p.m., 3 p.m. and 5 p.m… Mary’s, a new place on the Lower East Side, recently opened on Orchard Street. The restaurant and bar—inspired by the Queens restaurant that the founders’ great-grandparents once owned in the mid-20th-century—aims to capture the atmosphere of an old New York tavern. Food included Mary’s Pot Roast, named for the owners’ grandmother Mary. The cocktail lists includes modern classics like the Cosmonaut, American Trilogy, and Gin Gin Mule.

A bottle of Angostura is on my list of “emergency supplies” - water, advil, solar powered radio and Angostura. 😂

The Frank Morgan story is gold.