In the 1970s, my family, like many other American families, took summer vacations. We couldn’t afford to fly—we were a family of six—so we hopped inside our wood-paneled station wagon and drove off to whatever destination had been chosen that year: Florida, The Ozarks, Philadelphia (for the Bicentennial), the New Jersey shore, etc.

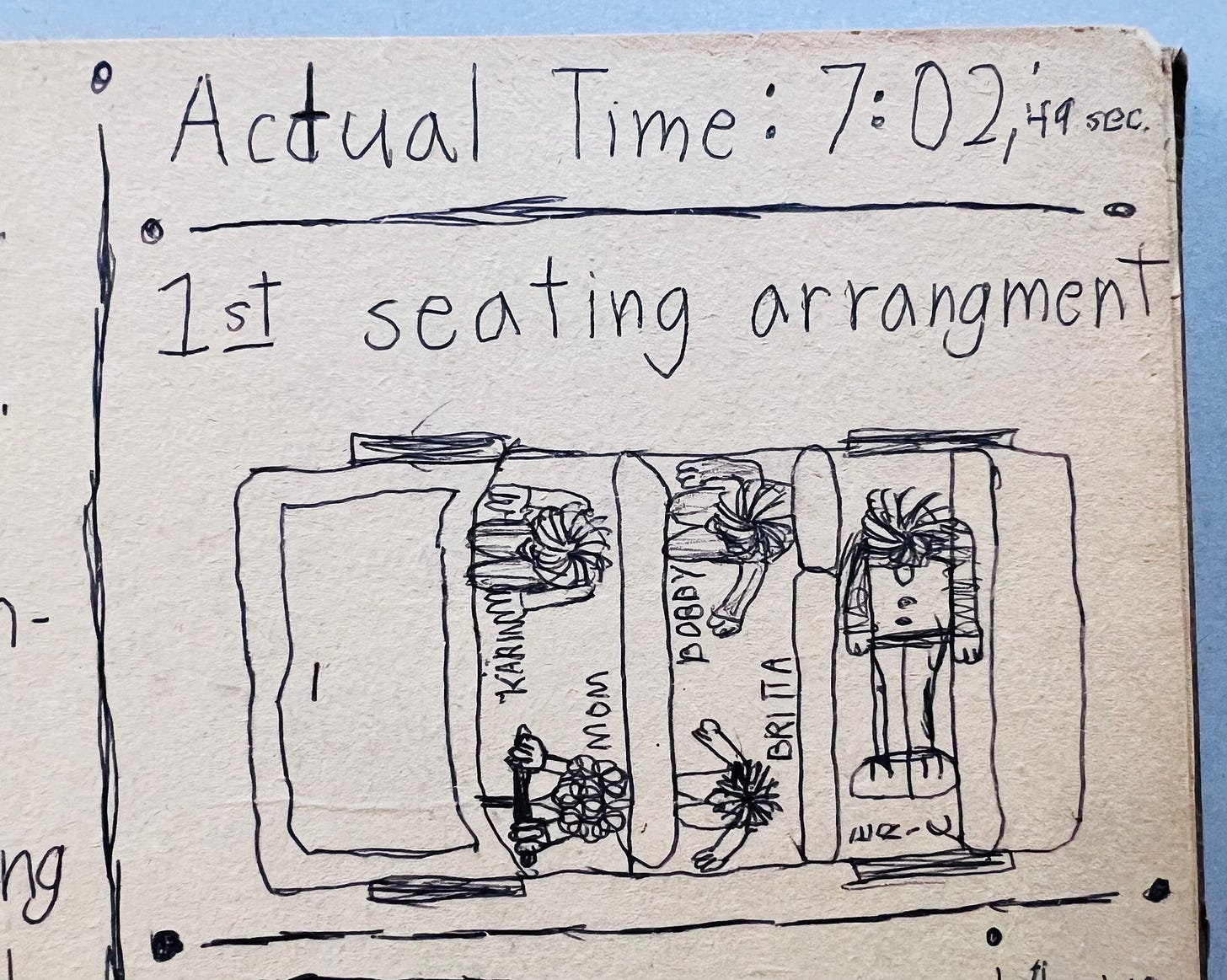

I maintained a highly detailed, anal-retentive scrapbook on each trip, recording each stop along the way, every restaurant we ate in, and the exact minute we passed a state line. I pasted in whatever matchbooks, napkins, menus and postcards I could gather. The leitmotif running through each book were birds-eye views of the changing seating arrangements in the station wagon. To a kid, such pecking orders are important. On a long road trip, everyone wants to sit in front and no one wants to sit in back; it was important to shift the seating every couple hundred miles in order to keep the peace.

I have been throughly mocked over these diagrams in the years since, by my siblings, relatives and friends. I get it. The seating maps are ridiculous, I admit. But I know why I made them. Any Virgo middle child—seeking order and justice in a senseless world—would understand.

I’ve held on to those scrapbooks and return to them from time to time. As I got older, I began to wonder if the places I visited on those trips still existed, and I’ve made attempts to revisit them. I haven’t had much luck. I went in search of the Red Garter, a sort of sing-along banjo beer hall in North Wildwood, NJ, but it had closed long ago. Ed’s Steak House was still operating in Bedford, Pennsylvania, until recently. But I waited too long to visit. The family that ran it closed it in January 2022 after 67 years in business.

But the Dutch Pantry still stood. Well, after a fashion.

The Dutch Pantry was a chain of family dining-style restaurants. Once there were 82 locations located across a dozen states. My family stopped at one along Interstate 76 in Pennsylvania on August 15, 1977. Here is my scintillating account of the meal:

At 1:20 we stopped at a restaurant called Dutch Pantry. It looked nice from the outside but it turned out to have slow service. I had the cheeseburger plate.

I was a tough critic even then.

Despite my less-than-glowing review, I had fond memories of that Dutch Pantry stop, ones that lingered over the ensuing decades.

A few years ago, I was driving some furniture from Wisconsin to Brooklyn along Interstate 80 in Pennsylvania when I saw a sign advertising a restaurant called Dutch Pantry. A bell rang in my head. I didn’t stop but, once I got home, I consulted my old scrapbook. Sure enough, there it was: Dutch Pantry. The one I saw on Interstate 80 wasn’t the one we had dined at in 1977, but it was proof that the chain still existed nearly a half century later.

But only just barely. Dutch Pantry has only two locations left, both along Interstate 80, and just miles from one another. One is in Clearfield and one is in DuBois. DuBois has a population of 15,500, Clearfield 6,000. Both towns are in Clearfield County.

Last month I was back on Route 80, this time driving some furniture from Brooklyn to Milwaukee. My stepson Richard and I had to eat lunch somewhere. Why not Dutch Pantry?

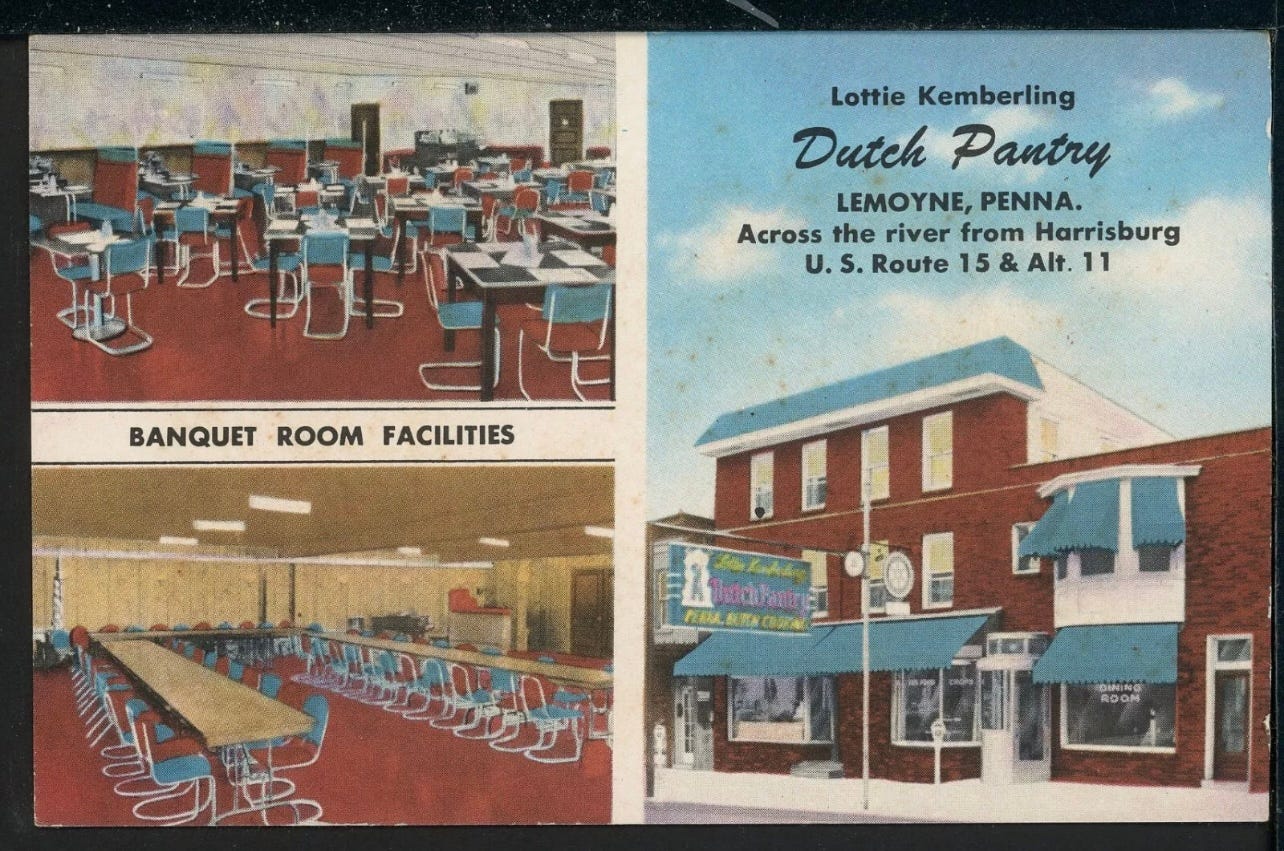

Dutch Pantry was founded in 1945 by Charlotte “Lottie” Kemberling and her son, Josiah “Jess” M. Kembering. Lottie began her food career by selling baked goods and salads at the farmer’s market. Eventually she built a brick and mortar headquarters, which transformed into a restaurant.

The first location was along U.S 11 near the tiny village of Selingsgrove in central Pennsylvania. The name of the place was meant to conjure up the sort of homey atmosphere and home cooking vaguely associated by the public with the Pennsylvania Dutch community. The Kembelings played up this image. As the brand expanded, each location was designed in bright red and white to look like a Pennsylvania Dutch barn. The sign outside was shaped like a windmill with rosemaling painted on it. The interior boasted a heavy-beamed ceiling and was anchored by a “pantry” where you could buy foodstuffs like jam and candy. The signature dishes included ham and bean soup and apple fritters.

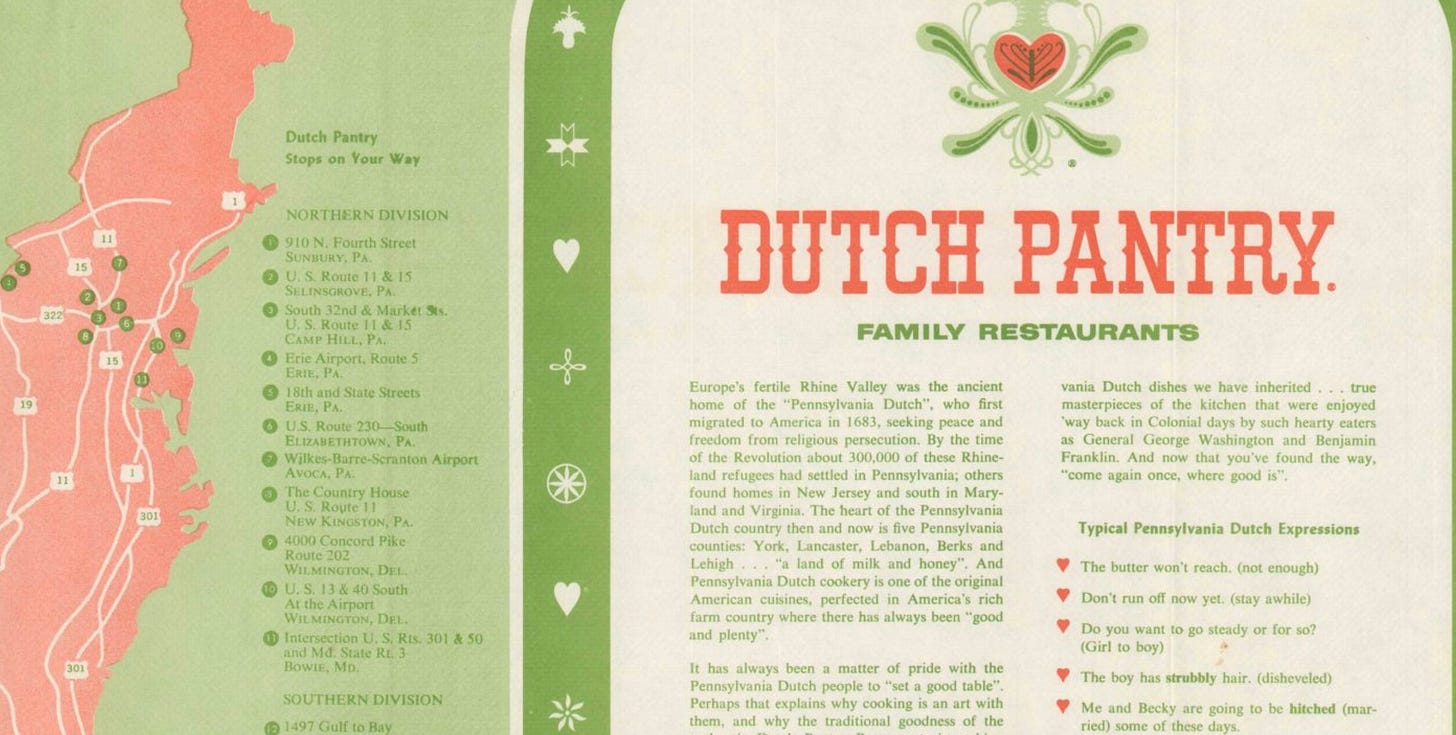

A 1963 pamphlet laid on the Americana pretty thick. It read:

There are few things in this world as tasty and satisfying as the Pennsylvania Dutch dishes we have inherited… true masterpieces of the kitchen that were enjoyed way back in Colonial days by such hearty eaters as General George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.

The restaurant’s slogan was “It’s Lots of Different Good,” an odd locution to be sure. Later it was replaced by the not-much-better, “Where Food Makes Friends.”

In 1963, Dutch Pantry had 16 locations in Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Florida, including a restaurant inside the new Wilkes Barre-Scranton airport. Eventually there would be 82 locations at the chain’s peak, with restaurants in Missouri, South Carolina and Texas.

In the early years, each restaurant was built near a gas station, so the chain was clearly geared toward the motoring set. It was very much in the tradition of fellow chains Howard Johnson’s, Stuckey’s and Horne’s.

The demise of Dutch Pantry follows the lines of many restaurant chains that didn’t make it in the cutthroat capitalism environment of the current century. Ownership changed several times, which each subsequent corporate overlord diluting the concept until Dutch Pantry was gutted of its original heart and soul and collapsed from neglect.

In the 1970s the restaurants were in the hands of C.P.C. International, which made Knorr soups and Mazola oil. C.P.C. planned 300 locations but fell short of its goal. By the 1980s, a firm called Rains International was operating the chain under a lease agreement with the Helmsleys, the infamous New York-based, real estate-owning family, which owned many of the physical buildings that housed Dutch Pantrys in Ohio. The Ohio franchises themselves were largely owned by the Standard Oil of Ohio (SOHIO), which attached Dutch Pantrys to their Hospitality Motor Inns (HMI) chain of motels.

Rains filed to sell its assets after a long battle in bankruptcy court. As a result, Raines stopped paying rent and dozens of Dutch Pantrys were kicked out of their homes by the Helmsleys.

The Dutch Pantry chain limped along toward near extinction after that.

The original location of Dutch Pantry was destroyed in a fire in 1963. Also lost in the fire was a large portrait of founder Lottie Kemberling. But, by then, Lottie was long gone, having died at age 62 in 1949, probably with little inkling of what would become of the business she started. She is buried with her husband Eugene not far from the original restaurant.

Her son Jess had retired to Florida by the 1960s and died in Palm Beach in 1979, also at the age of 62. His obituary described him as “a philanthropist, yacht broker and sportsman.”

Clearly, Dutch Pantry had been good to Jess.

Both the remaining Dutch Pantry locations opened in Jess’ lifetime. The DuBois Dutch Pantry opened in 1971. The Clearfield location arrived in 1974. (As recently as 2020, there was still a location in West Virginia.)

(Based on my scrapbook account, I’m guessing the original location my family stopped at back in 1977 was in Carlisle, just west of Harrisburg.)

Each remaining location is basically frozen in time, with the same windmill sign, the same decor and layout. As you enter, there is still the “pantry”-style gift shop, its shelves full of candles and old-style sweets and jams and such.

You’ve seen this set-up before if you’ve ever eaten at a Cracker Barrel. Cracker Barrel was founded in Lebanon, Tennessee, in 1969 and I’m pretty sure the founders stole their entire playbook from Dutch Pantry, which was a quarter-century old at the time. I read one recent online story where the writer asked a waitress what had happened to the Dutch Pantry dynasty. The waitress replied, “Cracker Barrel came through.”

Clearfield was the first of the two towns on our route west, so Richard and I stopped there. We walked through the “pantry” gift shop, passed the horseshoe-shaped diner counter and settled into a corner table. The ceiling was high with wooden rafters from which lighting fixtures hung. As for seating, there were a collection of wooden booths and round and square tables on the floors. The overall color scheme was brown. I doubt the design has been changed in decades. Most of the other customers were older than we, and obviously locals and regulars.

The menu is a time warp. Among the hearty selections are chicken-fried steak, steak and eggs, creamed chipped beef, grilled ham steak, liver and onions, turkey dinner, and pot roast. There were some nods to the tastes of our current times, included wings and a variety of salads. But the hot apple fritters were still on offer, as was the ham and bean soup, which the menu said was “from our original recipe which we believe (and are told) is the best bean soup there is.”

I hadn’t recorded having the ham and bean soup in my 1977 scrapbook, but I was sure I had had it. I was a big soup kid. It was my favorite kind of food. And I loved ham and bean soup, which my mother often made. It’s a kind of soup that was once quite common in American restaurants, but has fallen out of fashion today. I’m not sure why. It’s fantastic when done well.

Anyway, there’s no way I would not have ordered a cup of soup during one of our family’s few experiences in a restaurant. (My dad didn’t like to eat out. Or maybe just didn’t like to pay the tab for a meal for six.)

I had a huge sense memory upon swallowing that first spoonful of soup. It all came back to me. I remembered this ham and bean soup exactly. It was perfect.

My entrée was the chicken-fried steak and mashed potatoes, which were both on the small side and neither great nor bad.

We ordered the apple fritters to go and learned a valuable lesson. Apple fritters do not travel. You either eat them on the spot or don’t order them at all. That evening, at our hotel in Ohio, they were hard as a rock. I suppose that showed that they were fresh and had been handmade.

While paying the check, I spoke to the cashier, who had worked at the restaurant for many years. She said there was no competition from the Dutch Pantry in DuBois. The two owners knew each other and worked together to coordinate their recipes and menus so that customers at either restaurant enjoyed a consistent experience.

The pantry had nothing I wanted to buy aside from a bottle of house-made Dutch Pantry Sweet & Sour Salad Dressing. As far as I could tell, it was the only custom restaurant product that was for sale.

On the whole, our visit was a positive experience: homey interior, relaxed small-town vibe, above-average food, friendly service and good prices. Nearly every entree was $9-$13. If you are making the long drive across Pennsylvania on Interstate 80, it’s worth your time.

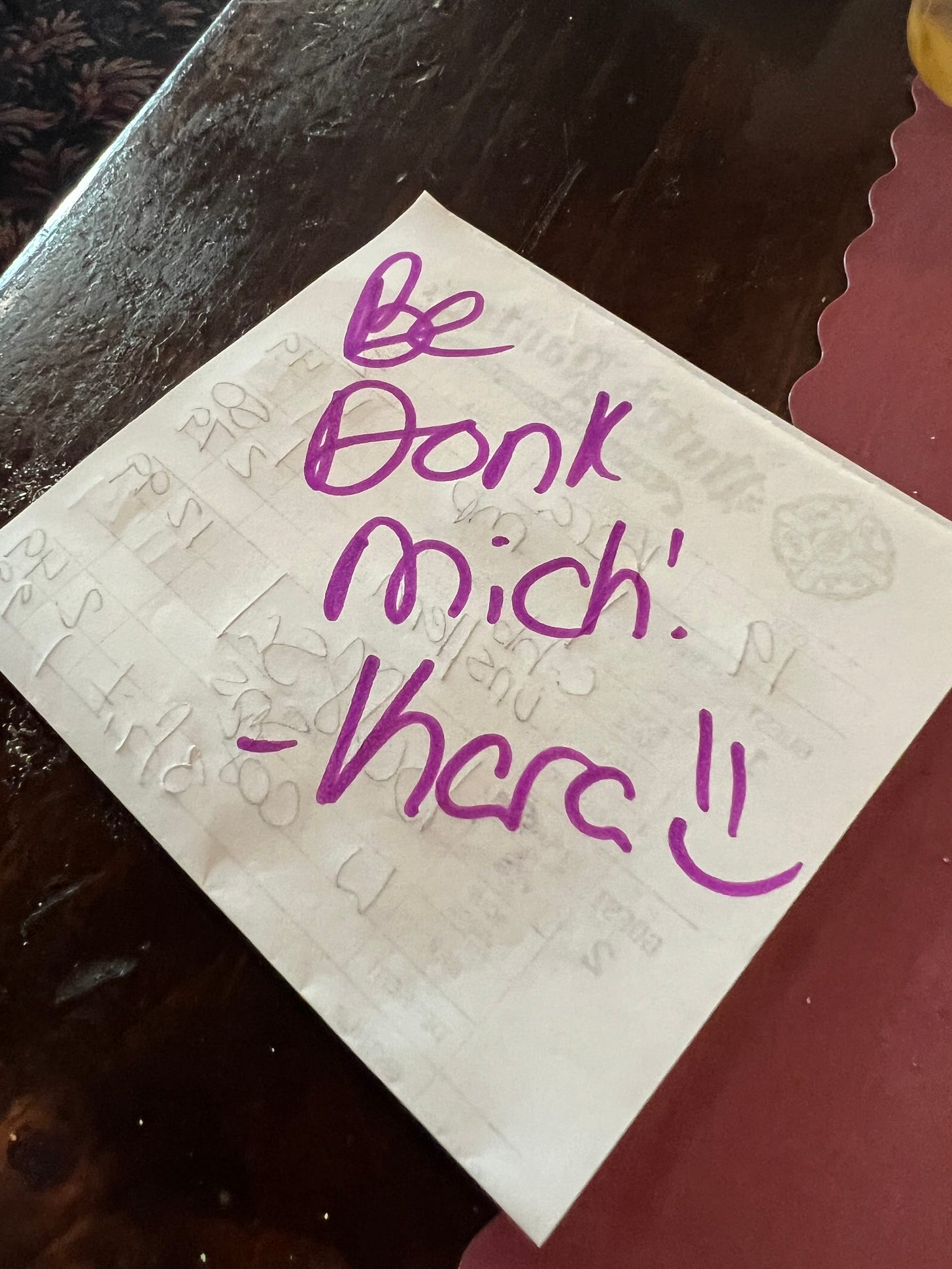

There was one last oddity that set Dutch Pantry apart from your average roadside dining experience. When the young waitress laid down the check, the words “Be Donk Mich!” were written on the back. The phrase is apparently Pennsylvania Dutch for “thank you very much.” Dutch Pantry writes it on the back of every check.

Odds and Ends…

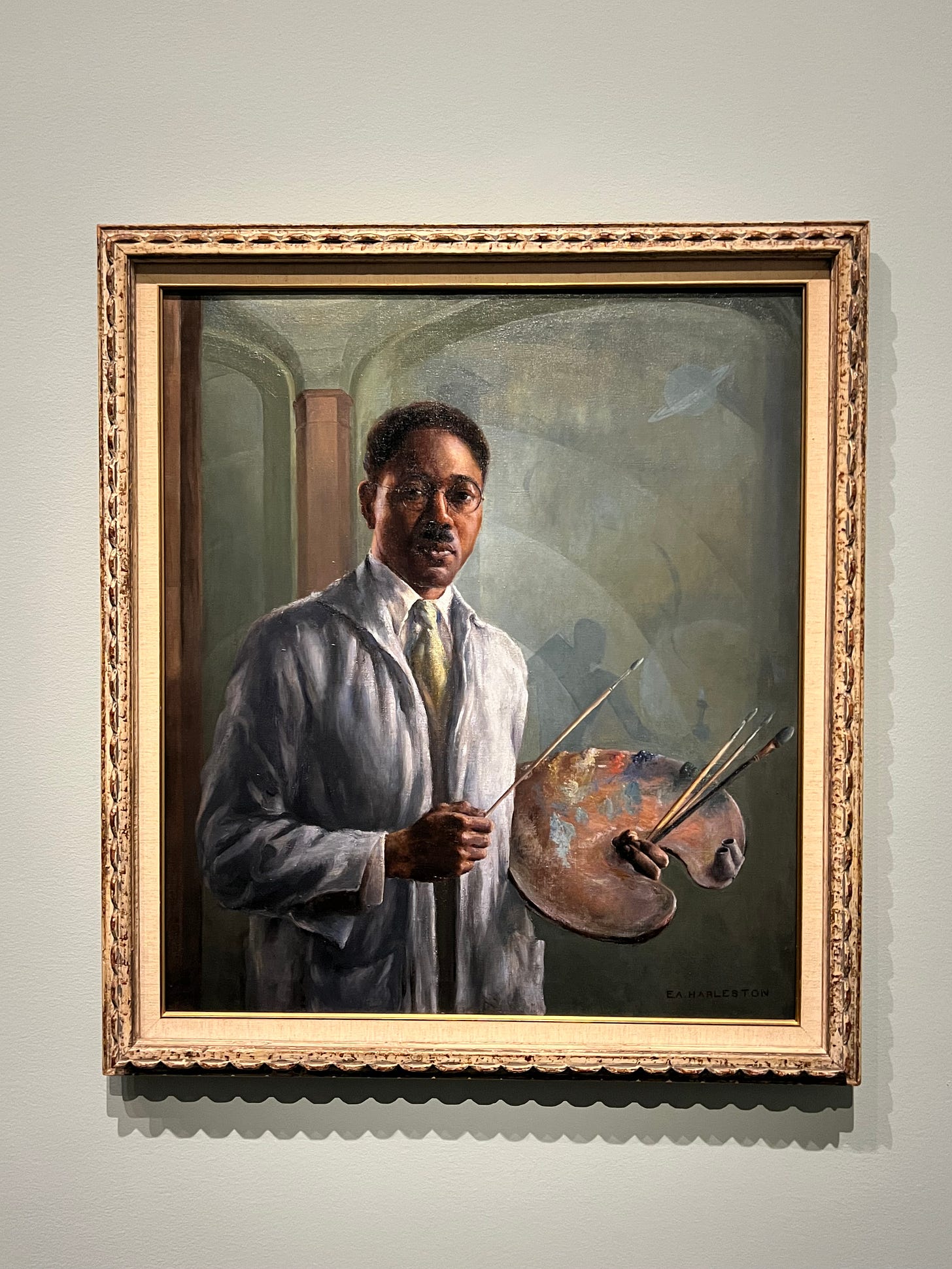

Basik, the cocktail bar in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, announced it would shut its doors on Aug. 12 after 13 years in business… The Spirited Awards were announced at the Tales of the Cocktail convention in New Orleans last week. Among the winners were Camper English for his release The Ice Book; Toni Tipton-Martin for her book Juke Joints, Jazz Clubs and Juice; Superbueno, which won Best New U.S. Cocktail Bar; Kapri Robinson of Allegory, in Washington, D.C., who was named U.S. Bartender of the Year; and Colin Asare-Appiah (a Bar Regular at The Mix), who took home the prize for Tales Visionary Award… Hanna Lee Communications (another Bar Regular), which represents many notable cocktail bars, announced the creation of an event called New York Bartender Week. The week-long celebration, which will run Nov. 18-24, will salute bartenders, bar backs, bar/restaurant owners and hoteliers in New York City and across New York State. It is described as “part consumer festival, part tourism and local economic development initiative and part educational trade symposium.”… “Sleeping Beauties,” the new exhibition at the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is recommended. The show focuses on how designers have been inspired over the decades by nature—including flowers, birds and bugs—to create their apparel. It runs through Sept. 2… Also at the Met, through July 28, is “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism.” While most studies of the Harlem Renaissance, which took place in the 1920s and ‘30, focus on writers such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, this show focuses on the lesser-known visual artists of the movement, including James Van Der Zee, Archibald Motley and Aaron Douglas… Devon Tarby, the former bartender who has been a partner in Gin & Luck, the company behind the Death & Co. chain of cocktail bars, as well as other venues, has exited the group after 14 years… My latest book, The Encyclopedia of Cocktails, will be translated into Portuguese… Koloman, the Austrian restaurant in Manhattan which is hosting week-long “Martini Residencies” all summer, will, beginning July 31, host author and lifestyle figure Matt Hranek.

I have 3 comments:

1. Check the date on the salad dressing.

2. Let’s make ham and bean soup this week!

3. I love those scrapbooks more than anything!

And the car seating sketches are great!