Making History: Roulade of Beef, August Lüchow

The Mix Revive's Robert's Favorite Pastime of Preparing Meals From Venerable Old Cookbooks.

You can’t visit vanished restaurants. You can read about them, look at photographs and study menus. You can even talk to older relatives who dined there back in the day. But you can’t know what they knew first hand: what the atmosphere was like, what kind of service the staff offered, how a meal there made you feel, the business’ particular magic.

However, you can experience their food, after a fashion. At least, you can for some of them, those that left behind a written account.

I own a lot of cookbooks. A good many of them are testaments to the fare of one particular famous restaurant, a place that no longer exists—indeed, did not exist when I bought the books years ago. I made these purchases to better understand iconic restaurants whose timeline on this earth sadly did not coincide with my own.

Most of these books begin with a little history of the restaurant, before the book gets into the recipes. This bit of text is largely why I bought the books in the first place. But, over time, I became interested in the recipes themselves. And, occasionally, I have tried to recreate entire meals from them.

I did this on a regular basis when I authored the blog Lost City in the aughts and early 2010s. Beginning in 2009, I ran an occasional column called “Recipes of the Lost City.” I’d attempt dishes once served at famed eateries, following the recipes to the letter, and then report on my success or lack thereof. I made Tavern Chestnut Dressing from Tavern on the Green; Chicken Manhattan House from Longchamps; Crabmeat a la Dewey from Gage & Tollner; Braised Striped Bass from Le Pavillon; and many more.

This pastime lasted only a year or so, petering out in 2010. Perhaps I traded in my interest in vanished meals for a similar one in vanished cocktails, as my career as a drinks writer advanced. But my interest in bygone restaurants remained, and I continued to add out-of-print restaurant cookbooks to my library.

Today—with Lost City long gone, but The Mix present and reporting for duty—it seemed like a good time to go back through that time portal into the kitchens of yesteryear. This is the first edition of a new occasional feature on The Mix called “Making History,” in which we’ll crack open those dusty accounts of a once-renowned restaurants and see if their bill of fare still holds up.

And this time there are two cooks in the kitchen.

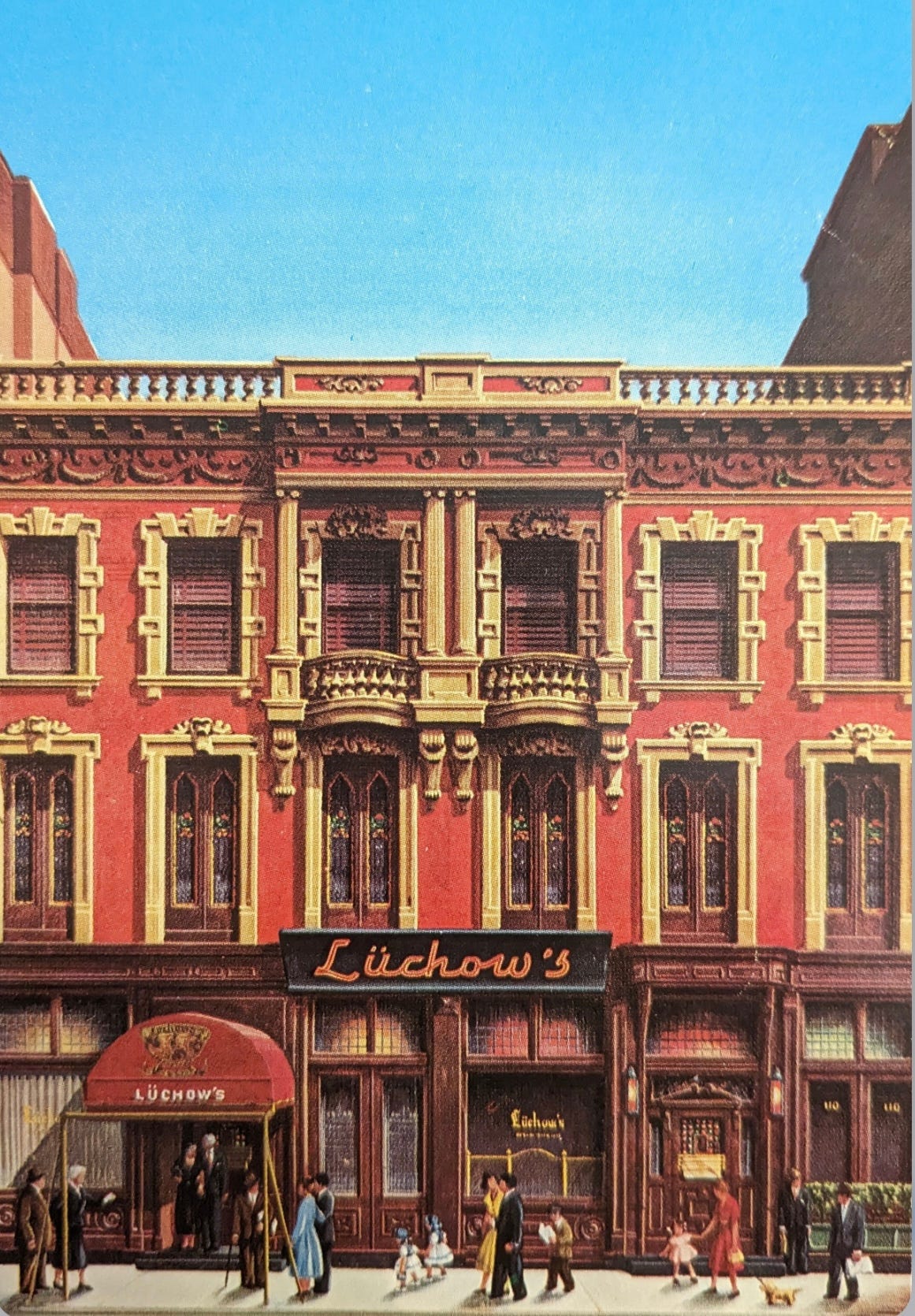

Few New York restaurants have managed to retain as strong a grip on the public imagination as Lüchow's, which stood on 14th Street near Broadway for exactly a century, from 1882 to 1982.

August Guido Lüchow, an immigrant from Hanover, Germany, opened his eponymous restaurant with the help of fellow countryman, William Steinway, who extended him a $1,500 loan. Steinway Hall was right across the street and the Academy of Music, a then-prominent opera house, was nearby.

Lüchow’s was the preeminent German restaurant in the city for most of its existence. And, given its choice location, it was also a show business hangout, a sort of Sardi’s during the days when Union Square was the center of New York's entertainment world. Regulars included most of the luminaries of the music world, including Oscar Hammerstein (the elder, not his son, the writing partner of Richard Rodgers); Victor Herbert, who founded the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) at a corner table; Tin Pan Alley tunesmith Gus Kahn, who wrote the lyrics to “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby” there; Enrico Caruso; Sigmund Romberg; Anna Held; Irving Berlin; Ignacy Jan Paderewski; and Richard Strauss.

Also a habitué was the inevitable “Diamond” Jim Brady, the financier who could not be kept from the tables of any noted restaurant of his day, and was often in the company of actress Lillian Russell.

Mary Kate and I have a special connection to Lüchow's. Both of our parents dined there. Mine ate there in 1964, during a trip to New York when my mother was pregnant with me (perhaps this is why, of all my siblings, I ended up in New York). Mary Kate’s parents dined anywhere that was anyplace in the New York City of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Their list was long and Lüchow's was on it.

Lüchow's German Cookbook came out in 1952. It was authored by Jan Mitchell, then owner of the restaurant, who was trying to reignite interest in his property and its legacy. The illustrations were by Ludwig Bemelmans, of Bemelmans Bar fame. I bought the book about twenty years ago. If you want a copy for yourself, they are easy to find online.

The dish we decided to tackle is one of the most complex in the book, and the one with the most ingredients: Roulade of Beef, August Lüchow. It’s even named after the founder. Hey, if you’re going to take this journey into the culinary past, you may as well go all the way back!

We also made the two side dishes that the book recommended accompany the roulades.

—Robert Simonson

So we begin.

Mary Kate here!

Whenever I begin cooking from these old books, I feel like I don’t speak the language. What I do know, is that what part of the language I do speak is missing a lot of nuance. The book makes assumptions that the recipe’s reader already knows certain things about how to cook then and—flash forward seventy-five years—I really don’t have a very good idea of what things were like back then.

How were the meals served? What did the finished product look like? There are no photos in the Lüchow's book. And somehow Bemelmans’ drawings aren’t very helpful. So, I googled things, I looked at old ladies’ magazines and books about entertaining. And, boy, did we luck out, because roulades, while tasty, are really unattractive! The bar was low.

I have never “rouladed” anything. I’m not sure why. My sister was the Buche de Noël girl (a traditional Christmas cake), and my friend Alison’s mom made Braciole, so I know what it means to have a flat food surface, cover it with something and then roll it up. But I hadn’t done it. So, when Robert and I decided to make Roulade of Beef, it was exciting.

We asked the butcher to cut up the beef into 6 pieces for us (aka step #1 in the recipe) and pound it out thin, though I would probably do this myself next time—maybe after we purchased sharper knives.

(Note: the key to this recipe is definitely in the prep. Measure everything, chop it and get it ready in bowls first. I got everything out—the pots and pans we would use; the serving platter; everything I could think of. Though we still ended up rummaging around for additional items at the last moment, you definitely don’t want to “prep as you go” here.)

The butcher didn’t pound the meat. At Staubitz, our preferred local butcher, when Robert asks them to pound the veal for schnitzel, it comes out beautifully thin. But we didn’t use Staubitz this time. So, we pounded the meat ourselves with a big wooden mallet until it was 1/4 inch thick. We then slathered it with the meat mixture, rolled the meat it and tied it with cooking twine. (step #2)

But then we realized that we forgot to add the encircling slice of salt pork to each roulade before we tied it. So we had to cut the strings and untied the roulades. Then we rolled on the (in our case) slices of bacon and tied it up again. At this time, I noticed we were getting better at tying.

After browning the meat on all side in the pot, we covered the roulades with the vegetables and the liquids. We really needed a bigger Dutch Oven than we had, or fewer roulades so the veggies could have browned too (step #3). We let it cook over the high heat for 10 minutes and then placed it in the oven for 45 mins (step #4). Step #5 was very difficult, as I did not want to throw out all the vegetables, which are there only to flavor the broth; I wanted to eat them out of the pot. (I’ll call this step #5.5—but I’ve gotten ahead of myself.)

While the roulades were cooking we moved on to the potatoes—which I would NOW like to remind you to begin BEFORE you start to roll the roulades because the potatoes have to soak in cold water for an hour. Also, “pro-tip”: the French Cutter you need to cut out the potato balls is just a big melon baller. Please have a good, sharp one ready (potatoes are much harder to ball than melons). Parboil the potatoes, and then brown them in fat. Once the potatoes are browning and getting crispy in the oven, it’s time to move on to the peas.

Making the peas was easy, except I wish we had had fresh peas. But it’s not pea season, and we couldn’t get any. So we used frozen. Oh, and I wish we had used more scallions. But I am glad we used more than a tablespoon of herbs.

I began to get very nervous as we waited for it all to finish in the oven. Was it going to be terrible? Did we just waste a Sunday afternoon? Just then, my son Richard, who was visiting that day, emerged from his nap and said, “Wow! That smells amazing!” and I knew everything would be alright.

And it was. In fact, it was delicious. Everything we had spent hours making was gone within 30 minutes. Lüchow’s lived again, for one night.

And Now the Recipes (also Odds and Ends follow):

Roulade of Beef, August Lüchow

2 pounds top round of beef

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon pepper

1 medium-size onion, chopped fine

1 shallot, minced

1 clove garlic, minced

1/4 pound beef, ground fine

1/4 pound veal, ground fine

1/4 pound pork, ground fine

1 tbsp chopped parsley

1 tsp chopped chives

2 slices bread soaked in milk

1/2 cup cream

6 think slices fat salt pork (or bacon)

1/4 cup flour

2 tablespoons beef fat, butter, or margerine

2 large onions slices thin

2-3 carrots slice thin

1/2 teaspoon powdered cloves

1/2 teaspoon thyme

1 bay leaf

2 tomatoes, peeled and chopped

1 cup burgundy wine

1 cup veal or beef stock

Wipe top round with damp cloth. Cut beef in 6 slices about 2 1/2 inches by 4 inches and 1/2 inch thick. Place on board and pound well to about 1/4 inch thickness. (Or have your butcher do it.) Season with salt and pepper.

Combine medium onion, shallots, garlic, ground beef, veal and pork, parsley, chives, bread and cream. Mix well. Spoon generous amount of mixture onto each piece of beef. Roll up beef, wrap with slice of salt pork or bacon, and tie with cooking twine or fix together with toothpicks. Sprinkle each roulade lightly with flour.

Preheat oven to 350 degrees Fahrenheit. Grease deep heavy pot or Dutch oven with beef fat, butter or margarine. Place roulades in the pot. Cook over high heat to brown on all sides. Cover roulades with sliced onions and carrots. Add cloves, thyme and bay leaf. Add tomatoes, wine and stock. Cover and cook over high heat for 8 to 10 minutes.

Set covered pot in oven and cook until roulades are well done, between 30 and 45 minutes.

Remove roulades from oven and place rolls on warmed serving dish. Remove skewers or twine. Set pot on high heat and boil sauce rapidly to reduce it. Strain the vegetables from the sauce. (You discard the vegetables.) Reheat the sauce if necessary, and pour over the roulades.

Serve with hot vegetables such as glazed onions, new peas and Parisienne Potatoes. (Recipes below.)

Potatoes Parisienne

8 large new potatoes

2 tbsps butter or bacon drippings

Salt

Paprika

Wash potatoes; peel. Cover with cold water and let stand 1 hour.

Drain and cut potatoes into balls using a French cutter. (A large melon baller will do.) Cover potato balls with boiling salted water and cook until almost tender, about 25 minutes. Drain

Preheat oven to 400 Fahrenheit. Melt butter or drippings in a frying pan; cook potatoes until light brown. Season with salt and paprika. Place in shallow pan in hot oven to crisp and brown further. Add more butter to finished potatoes if needed. Serves 6.

New Peas With Onions, Fines Herbs

1 pound fresh young peas (or frozen, if fresh not available)

6 young scallions

1/2 tsp salt

Dash of pepper

1 tbsp sugar

2 tbsps butter

3/4 cup boiling water

1 tbsp mixed chopped parsley, tarragon, chives and chervil

Preheat oven to 375 Fahrenheit. Wash and shell peas. Wash scallions; cut white part in 1-inch lengths. Combine with peas in small casserole dish. Add salt, pepper and sugar. Mix. Add butter and flour. Mix. Add water. Cover and place in over until peas are tender, about 30 minutes. Stir herbs into peas. Serve from casserole. Serves 3 to 4.

Odds and Ends…

Bartender and brand ambassador Chris Patino passed away on Oct. 18 after a years-long battle with cancer. As an early brand ambassador of Plymouth gin and later working within the larger Pernod Ricard liquor conglomerate, Patino was a one of the prominent figures during the early cocktail renaissance on the liquor brand side of things. He was also visible as the flamboyant MC of the Speed Rack cocktail competitions during the charitable organization’s early years. He was the founder of a trade-focused marketing agency, Simple Serve, and a partner at Californian cocktail bar, Raised by Wolves. He was named 2023's Best U.S. Bar Mentor by Tales of the Cocktail’s Spirited Awards. Patino is survived by his wife Heather and three children. He will be missed.… Eric Simonson (my brother) will be hosting two book events in the Midwest in November. First up is a discussion of Chicago theater in the ‘80s and ‘90s and his new memoir Between the Lines, held on Nov. 11 at 7 pm at Chicago Dramatists. The second is Nov. 12 at 6:30 at Boswell Books in Milwaukee, where he will discuss his book with Mark Clements, the artistic director of Milwaukee Repertory Theater.… Friday lunch and weekend brunch is back at Gage & Tollner in Brooklyn. Dishes include a Golden Mushroom Rarebit, Fried Ipswich Clam Po'Boy, Hot Ham & Cheese, a hamburger and steak and eggs… Adam Montgomerie has left his position as beverage director at the New York branch of Hawksmoor. He has been at Hawksmoor since the restaurant opened. No word on what he will be doing next… Julie Reiner is spearheading Blitzen’s, a new Christmas pop-up bar that will debut this fall at various Omni Hotels and Resorts, including the Omni Berkshire Place. Blitzen’s will open to the public Nov. 15 at 13 different locations… Underberg, the longstanding, cultish brand of German bitters, has introduced a rare line extension, Underberg Espresso Herbtini, which is a mix of the bitters and espresso. I guess everybody wants some of that Espresso Martini money… Noted whiskey writer Lew Bryson is working on a new book about whiskey… The 50 Best Bars list for 2024 was announced in Madrid last week. Handshake Speakeasy of Mexico City topped the list. Sips in Barcelona, last year’s No. 1, dropped to the No. 3 spot. The top-placing U.S. bar was Double Chicken Please at No. 14. Among the special awards, Caretaker’s Cottage in Melbourne won the Michter’s Art of Hospitality Award and Monica Berg won Industry Icon… The Holiday Punch Release Party will take place at Bryant’s Cocktail Lounge in Milwaukee on Nov. 27. The old cocktail bar is famous for its holiday punch, which is only servedduring the holidays.

Wonderful new feature. Great column and looking forward to the next instalment.

Whoa!😍